Previous

UNDER

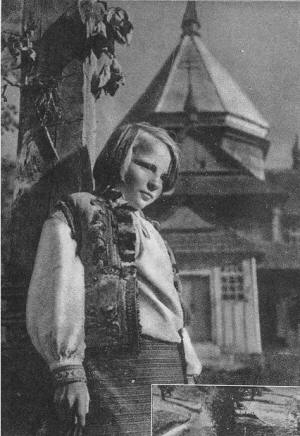

THE CARPATHIANS

HOME OF A FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

Past Without Glory

Next

Previous

| UNDER THE CARPATHIANS HOME OF A FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

Past Without Glory | Next

|

The history of Carpatho-Ukraine is a plain and pathetic tale. This land of simple peasants cannot boast of any feats worthy of a national epic. it had no valiant knights, no mighty rulers, no great causes to live, fight, or die for. There were no triumphs, no glorious failures in its past ; no notable achievements in culture or religion, science or industry. The country has never had a really independent existence. Its history is not the history of a State ; it is rather the melancholy story of a neglected, down-trodden people who only recently began to emerge from their age-old wretchedness.

According to the earliest available records from the end of the ninth century, part of Carpatho-Ukrainian territory appears to have been incorporated in the great Bulgarian Kingdom. Some historians have assumed that a number of Ukrainians lived there side-by-side with the Bulgarians, but there is little evidence to support this claim. In the tenth century the nomadic Magyars, in their westward drive from Asia, overran the Danubian plain and drove out the Bulgarians. They had probably been nominal rulers of the lowlands of present-day Carpatho-Ukraine before the first few Ukrainian colonists moved in from neighbouring Galicia. But a more systematic colonisation on a larger scale was initiated in the thirteenth century, when the whole Hungarian realm was devastated by the Tartars and its population decimated. Ukrainians and, to some extent, Rumanians and Germans were encouraged to settle in the thinly-populated valley of the river Tisa and later, also, in the practically uninhabited mountainous parts of Carpatho-Ukraine.

According to the earliest available records from the end of the ninth century, part of Carpatho-Ukrainian territory appears to have been incorporated in the great Bulgarian Kingdom. Some historians have assumed that a number of Ukrainians lived there side-by-side with the Bulgarians, but there is little evidence to support this claim. In the tenth century the nomadic Magyars, in their westward drive from Asia, overran the Danubian plain and drove out the Bulgarians. They had probably been nominal rulers of the lowlands of present-day Carpatho-Ukraine before the first few Ukrainian colonists moved in from neighbouring Galicia. But a more systematic colonisation on a larger scale was initiated in the thirteenth century, when the whole Hungarian realm was devastated by the Tartars and its population decimated. Ukrainians and, to some extent, Rumanians and Germans were encouraged to settle in the thinly-populated valley of the river Tisa and later, also, in the practically uninhabited mountainous parts of Carpatho-Ukraine.

At first the settlers were relatively well-off and enjoyed certain privileges granted them by the Crown and the land-lords, who were anxious to increase their own income from their large, but mostly undeveloped, Carpathian possessions. But as from the end of the twelfth century the influence of the Hungarian Crown became firmly established, the Magyar privileged classes got the upper hand in the lowlands and started whittling away the concessions granted to the immigrants. Gradually, but inexorably, the position of the Carpatho-Ukrainian settlers deteriorated.

The Turkish invasion and occupation of the greater part of Hungary in the sixteenth century set on foot a series of events which plunged Carpatho-Ukraine into untold misery. For nearly two centuries the country was ravaged by recurring outbursts of rebellion and violent fighting. Supported by the Turks, the Protestant noblemen of Transylvania (eastern Hungary) rose in arms against the absolutism of the Catholic Habsburg dynasty, to assert their religious freedom and political privileges. Much of the righting took place on Carpatho-Ukrainian soil ; some of its districts changed hands time and again, towns were repeatedly sacked, whole villages were burnt to the ground, the population was decimated and much live-stock was destroyed. The western part of the province suffered most and its economic life was ruined. To top it all, the feudal landlords e remorselessly squeezed the peasant serfs dry. Subjection and poverty, however, did not prevent the people from preserving their national customs, their peasant culture and their native tongue. In the seclusion of the mountains to which they had to retreat from the fertile lowlands, they managed to lead their own traditional life. The destiny of the Hungarian kingdom meant little to them. Perhaps the only exception was King Matthias Corvinus, who during his reign exempted them from paying taxes and tithes. Many Carpatho-Ukrainians served under his banner during the war against the Turks, and he figures frequently in national songs and tales.

The freedom given to the Carpatho Ukrainians to express their beliefs and customs was hniited. Religion was the mainstay of their racial consciousness. They belonged t( the Russian Orthodox Church and remained within its orbit for a number of centuries, even though the Church was never looked upon with favour by the Habsburgs from the time when they became kings of 1-lungary in 1526. The ancient Slavonic liturgy of the Orthodox Church was a spiritual bond which linked them to the historical traditions of then kinsmen in Poland and Russia and contributed, to some extent, towards their isolation from the cultural developments in western Europe ; and it was this isolation which was partly instrumental in conserving their national character.

In the middle of the seventeenth century the Habsburgs, true to their customary policy in matters of religion, launched an offensive against the Orthodox Church, with a view to establishing the ecclesiastical authority of Rome also in the eastern parts of their realm. Under official patronage the Greek Catholic Church was set up in 1646. Its followers acknowledged the Pope as their head and recognised the supremacy of Rome in all questions of dogma, but they were allowed to retain the eastern rites.

In the western part of the province the conversion from the Orthodox to the Greek Catholic denomination proceeded apace. The clergy, including the Bishop of Mukacevo, accepted the new state of affairs hoping to improve their standing, while the greater part of the peasantry hardly noticed the change, because the new Church retained the old Slav liturgy and was allowed independence in matters of habit and custom. The eastern part of the country, however, remained immune from this development for some consider-able time. This was largely due to its close association with Transylvania where unlike the rest of Hungary, religious liberty was protected by law till 171 1 . Only when the Habsburgs succeeded in breaking the last revolt of the recalcitrant Transylvanian nobility did the Greek Catholic Church make headway also in eastern Carpatho-Ukraine. Nevertheless, opposition to the conversation was considerable, particularly when it became evident that the official Church was to be used as a political weapon.

In the western part of the province the conversion from the Orthodox to the Greek Catholic denomination proceeded apace. The clergy, including the Bishop of Mukacevo, accepted the new state of affairs hoping to improve their standing, while the greater part of the peasantry hardly noticed the change, because the new Church retained the old Slav liturgy and was allowed independence in matters of habit and custom. The eastern part of the country, however, remained immune from this development for some consider-able time. This was largely due to its close association with Transylvania where unlike the rest of Hungary, religious liberty was protected by law till 171 1 . Only when the Habsburgs succeeded in breaking the last revolt of the recalcitrant Transylvanian nobility did the Greek Catholic Church make headway also in eastern Carpatho-Ukraine. Nevertheless, opposition to the conversation was considerable, particularly when it became evident that the official Church was to be used as a political weapon.

The ideal ‘ of national self-determination stimulated by the French Revolution found but little response in the Carpathian. province. in 1848, when the Magyars tried to overthrow the Habsburg régime and set up a Magyar national State, the Carpatho-Ukrainians stood by the Habsburgs. The uprising was quelled. Partly in order to punish the rebellious Magyars, the Imperial Government in Vienna granted the Carpatho-Ukrainians certain rights and united the four administrative counties of their country in a single administrative unit.

It seemed that Carpatho-Ukraine was, at last, on the threshold of a satisfactory national development; but any such hopes were soon dashed. Less than twenty years later the Vienna Government agreed to a far-reaching autonomy for the whole Danubian area under the leadership of the Magyars, and this put a stop to the national aspirations of all non—Magyar people living there. The Hungarians asserted their now enhanced supremacy with a vengeance, aiming at no less than the denationalisation of all minorities.

The dissatisfaction at the turn of events gave rise to a wave of Russophilism in Carpatho-Ukraine. The presence of Russian troops during the Magyar uprising of 1848 was well remembered, and some patriotic leaders looked to the Tsar for national salvation. It was impressed on the people that they belonged to the great Russian family ; educated men strove to spread interest in Russian literature, culture and folk-lore, and poets, like Duchnovic, used in their writings a language which differed but little from pure Russian.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century yet another national movement was introduced in the province. This time it was Ukrainian separatism, the advocates of which insisted on the specific national character of the Ukrainians as distinct from the Russians. The spokesmen of this movement employed the language of Kiev for their literature, and their aim was that one day all Ukrainians living in Russia, Austro—Hungary and Rumania should be united.

Before the first World War this movement made little headway in Carpatho-Ukraine. The bulk of the uneducated peasants simply did not understand what it was all about, and their lack of cultural and political ties with the Ukrainians beyond the Carpathians made it easy for Magyar propaganda to foster the local patriotism of the Ruthenians as the inhabitants of Carpatho-Ukraine were then called. The Magyars insisted that the Ruthenians had a distinctive national character of their own and that their language which is, in fact, no more than a. Ukrainian idiom- -was a special language. In order to make this propaganda more effective, the Hungarian authorities did their utmost to close the frontier to any persons who might have spread the pan-Ukrainian movement to the south of the Carpathians, and repressed all attempts at its expression within the province itself.

The pro-Russian movement would hardly have fared better but for the fact that its promoters had hit upon the idea of making an appeal to the peasants through religion. The plan was to persuade the people to return to the fold of the reduced and impoverished Russian Orthodox Church. As the Tsar was the supreme head of the Church, it seemed a fairly easy task to win the religious converts over to the pro-Russian movement.

The scheme worked. Mass conversions took place and whole villages to a man left the official Greek Catholic Church. The growth of the movement so alarmed the authorities that they decided to strike. Police detachments swooped upon the most implicate d villages, plain-clothes s men spied out the ringleaders, large-scale arrests were made and legal proceedings instituted against those who were suspected of having been in touch with subversive elements” in Galicia and Russia. The result was the mass trial at Marmaros Sziget, where 94 priests and peasants were charged with high treason. This trial ended with 32 of the accused being heavily fined and sentenced to imprisonment.

A few months later, the first World War broke out and the Government reaped the fruit of its oppressive policy.

The sympathies of many Carpatho-Ukrainians were with the Russians, and in order to prevent a major revolt the Hungarian authorities imposed vigilant surveillance and preventive arrests. When the Tsarist army temporarily penetrated the Carpathian passes, it was given a great welcome by the local population.