Previous

UNDER

THE CARPATHIANS

HOME OF A FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

Precious Salt

Next

Previous | UNDER THE CARPATHIANS HOME OF A FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

Precious Salt | Next

|

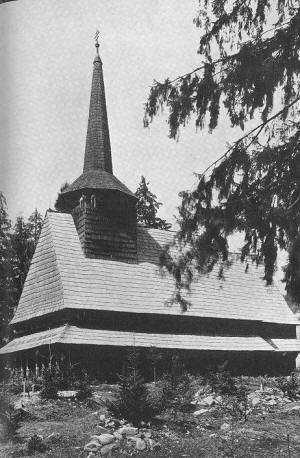

RIGHT on the Rumanian frontier lies a small township called Slatina Mines. Its position affords a delightful view of the mountains, but the township itself is not much to look at. few modern steel and concrete buildings contrast oddly with the unpaved main street, and a number of villas, some of them in spacious tree-clad gardens, look rather unusual next to a jumble of debased and urbanised wooden dwellings of the peasant type. But economically this gallimaufry of a township is of considerable importance.

RIGHT on the Rumanian frontier lies a small township called Slatina Mines. Its position affords a delightful view of the mountains, but the township itself is not much to look at. few modern steel and concrete buildings contrast oddly with the unpaved main street, and a number of villas, some of them in spacious tree-clad gardens, look rather unusual next to a jumble of debased and urbanised wooden dwellings of the peasant type. But economically this gallimaufry of a township is of considerable importance.

There are rich deposits of mineral salt in its vicinity which share with the vast forests the pride of place in the country’s economy. These mines are said to have been worked for several centuries, and between the two World Wars more than 120,000 tons of salt a year were mined, most of which was exported to the neighbouring countries. Three long trains, fully loaded with salt, would leave Slatina Mines every day, their principal destinations being Czechoslovakia and Germany .

In most countries salt is cheap and plentiful. But to the poor peasants and wood-cutters of Carpatho-Ukraine it was a luxury which they could ill afford. To season their simple and meagre food, they had to scrape and shift for themselves as best they could. In older times the uplanders used to set out with their carts on a long journey to some salt-water pool or well to fill a barrel or two with brine which would last them a number of months. But one day they had enough of it. “ If there is plenty of salt for Germany, there must be enough for us,” they said, and decided to take their carts to Slatina Mines to fetch the real stuff - the rich whitish salt dug from the mines.

In most countries salt is cheap and plentiful. But to the poor peasants and wood-cutters of Carpatho-Ukraine it was a luxury which they could ill afford. To season their simple and meagre food, they had to scrape and shift for themselves as best they could. In older times the uplanders used to set out with their carts on a long journey to some salt-water pool or well to fill a barrel or two with brine which would last them a number of months. But one day they had enough of it. “ If there is plenty of salt for Germany, there must be enough for us,” they said, and decided to take their carts to Slatina Mines to fetch the real stuff - the rich whitish salt dug from the mines.

In the course of time mass expeditions to Slatina became a regular occurrence. From the remotest villages in the mountains carts would set out once or twice a year to trundle on for days to the distant place where they were sure to find salt in plenty. On the way they would be joined by more carts, till finally a vast train of vehicles was moving along the roads, so vast, that it would take hours to clear a crossing.

When they reached Slatina Mines the peasants would hurl themselves on the salt they found lying on the ground by the trucks, from which it had fallen while they were being loaded. The bolder spirits cut the barbed wire fence behind which the huge stocks of salt were stored, and helped themselves to as much as they wanted.

When they reached Slatina Mines the peasants would hurl themselves on the salt they found lying on the ground by the trucks, from which it had fallen while they were being loaded. The bolder spirits cut the barbed wire fence behind which the huge stocks of salt were stored, and helped themselves to as much as they wanted.

At first this pilfering was relatively easy. True, guards used to turn up soon after the arrival of the carts, but. they were powerless against the vastly superior numbers of the invaders. And so the first expeditions met with success which encouraged further attempts on an increasingly large scale.

The State authorities decided to intervene. On the approach of each expedition a strong detachment of military police arrived on the spot. But the peasants would not be deterred. They were determined to get the salt and struggled hard to load their carts whatever the police might do. It the gendarmes tried to unload one of the carts, scores of peasants set on them, and a pitched battle was fought. As a rule, a number of the most aggressive troub1e-makers were arrested, while others had their names taken down to be sent to prison later on.

But even this failed to stop the expeditions . To the Carpatho-Ukrainian peasants a cart-load of salt, which would last them a year, was worth the risk of spending a fortnight, or even a month, in prison. And after all, what was wrong with prison ? The inmate got his food free of charge, he could have a good rest, and the cell was more comfortable than a wretched wooden hut, particularly it he had the rare luck to be sent to the up-to-date gaol at Uzhorod. Sometimes when there. was urgent work to be done in the fields, the sentence was deferred, and a couple of weeks later the offender would come forward of his own accord to serve his term.

To prevent these yearly disturbances at the salt mines, the authorities decided to make the best of a bad bargain. They announced that once a year the poor would he allowed to fetch a cart-load of salt. This compromise was completely successful. The expeditions to Slatina Mines were staggered; each district was allotted a definite day on which the peasants could bring their carts along and peace was restored.