Previous

UNDER

THE CARPATHIANS

HOME OF A FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

The Gipsies

Next

Previous | UNDER THE CARPATHIANS HOME OF A FORGOTTEN PEOPLE

The Gipsies | Next

|

THE modern city of Uzhorod had a unique feature – a school for Gipsies. It was not the Gipsies themselves who wanted the school ; in fact, they would have been the last people in the world to ask for it. When the school was set up by the Czechoslovak authorities, they had to bribe the Tsiganes into sending their children to it. This was done by providing meals for the pupils which soon proved to be a tempting bait. But there still remained the problem of teaching them. The little Gipsies were astonishingly quick-witted, but their attention was ever vacillating and they seemed unable to concentrate on any subject, except music, for more than a couple of minutes.

THE modern city of Uzhorod had a unique feature – a school for Gipsies. It was not the Gipsies themselves who wanted the school ; in fact, they would have been the last people in the world to ask for it. When the school was set up by the Czechoslovak authorities, they had to bribe the Tsiganes into sending their children to it. This was done by providing meals for the pupils which soon proved to be a tempting bait. But there still remained the problem of teaching them. The little Gipsies were astonishingly quick-witted, but their attention was ever vacillating and they seemed unable to concentrate on any subject, except music, for more than a couple of minutes.

Then, the educational authorities were anxious to train the youngsters to keep clean, an innovation which most of these dark-skinned people apparently found unpalatable. They had a native dislike of baths, inoculations and haircuts. The Czechs, who were anxious to improve hygienic conditions in the country, had literally to hunt for some of those obdurate nomads who were afraid that a wash or a haircut would bring about their death . The youngsters were not so difficult, for in spite of much screaming and yelling they could be bribed into being washed and combed at school. A bribe was usually the most effective argument with the Gipsies.

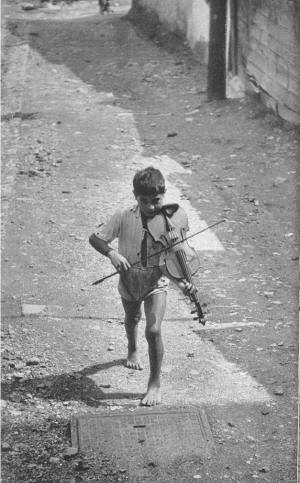

[Young Gipsy musician]

But their interest could be aroused in other ways too. One day an English linguist who knows almost every language under the sun, visited the Gipsy school at Uzhorod and was allowed to address a meeting of the pupils and their parents in Romany, their strange and primitive mother tongue. He enlarged on the importance of education for anyone who wanted to get on in the world and exhorted his listeners to improve their knowledge by reading books written in their native language. " But there are no such books ," the audience demurred. Nonplussed, the English-man produced a booklet on the deeds of the Apostles which he himself had translated into Romany. “ Here is a booklet in your own tongue ; I shall give a copy to anyone who will read a passage to me. ‘ The elders shook their heads - most of them had never learned to read and, anyway, the whole thing was sheer moonshine. The youngsters, though a little incredulous and diffident, were more willing the promise of a free copy was a temptation. One after the other they set out reading a passage each from the booklet. They read somewhat haltingly because they had never before seen anything printed in their native tongue, but they succeeded and everybody understood. The little Gipsies were, of course, very proud of their feat and pestered their English visitor for more books in Rornany the whole time he stayed with them.

This English gentleman appears to have hit it off with the Gipsies of Uzhorod. He was repeatedly invited to their homes incredibly dirty and wretched hovels and they treated him like one of their own. One day, a Gipsy youth asked him whether he was married. The answer being no, the boy presently introduced him to his sister, a personable girl with deep olive skin and large, flashing brown eyes. She greeted him with a broad grin of invitation, exposing her ivory teeth. To enhance her value she produced a handful of coppers, obviously procured by begging, and assured her involuntary and unwilling suitor that more would be forthcoming. He had a narrow escape from the impending mésalliance.

This English gentleman appears to have hit it off with the Gipsies of Uzhorod. He was repeatedly invited to their homes incredibly dirty and wretched hovels and they treated him like one of their own. One day, a Gipsy youth asked him whether he was married. The answer being no, the boy presently introduced him to his sister, a personable girl with deep olive skin and large, flashing brown eyes. She greeted him with a broad grin of invitation, exposing her ivory teeth. To enhance her value she produced a handful of coppers, obviously procured by begging, and assured her involuntary and unwilling suitor that more would be forthcoming. He had a narrow escape from the impending mésalliance.

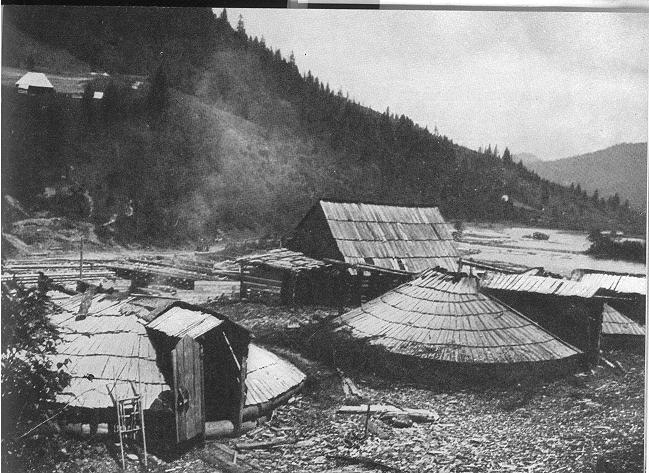

it has to be pointed out that the girl belonged to a fairly respectable “ middle-class “ family, as did more or less all the Gipsies living in special settlements on the outskirts of Uzhorod and other larger towns of Carpatho-Ukraine. Unlike their nomadic kinsmen who roamed about the country, the settlers were registered with the police, had their own “ mayor “ and were, as far as the law was concerned, fully fledged citizens with tile right to vote. They earned their living chiefly as horse-dealers, basket-makers and inferior masons. Their services were used by the peasants who wanted cheap labour, while town people refused to employ them. Although only casual labourers, they looked down upon their roving kinsmen, who had no legal status and lived mainly by begging, thieving and sooth-saying. The class-superiority of these settlers did not, however, prevent them from supplementing their very meagre wages by having recourse to less respectable practices. when a Gipsy was hired for work he took his wife and children with him and they all lent a helping hand ; naturally enough, the “ helping “ hand sometimes snatched a “ stray” hen of which the Gipsies made a very delicious meal.

In spite of their bad reputation, it would be wrong to assume that all Gipsies are dishonest. The following two incidents show that integrity is not alien to this dark-skinned oriental race. The authenticity of these incidents is vouched for by an Englishman who, intending to buy a turkey in the local market, enlisted the support of two Gipsy boys. The boys, who knew all about fowls, picked out a capital bird, but when it came to paying the Englishman found that he had only banknotes in his wallet. He asked the boys to get some change for him, and the two Gipsies made off with one of his notes. He waited and waited, and after half-an-hour he nearly gave up the money for lost, when suddenly the boys came back panting. “ Sorry, sir, to have kept you waiting so long, said the elder of the two, and explained that no less than ten shopkeepers had refused to give them change. believing that the boys had stolen the banknote. Delighted with the happy ending, he rewarded boys accordingly and became a staunch champion of the Gipsies trustworthiness. A few days after this incident he had the courage of his convictions and staked a wager on it. And, believe it or not, he won the bet.

In spite of their bad reputation, it would be wrong to assume that all Gipsies are dishonest. The following two incidents show that integrity is not alien to this dark-skinned oriental race. The authenticity of these incidents is vouched for by an Englishman who, intending to buy a turkey in the local market, enlisted the support of two Gipsy boys. The boys, who knew all about fowls, picked out a capital bird, but when it came to paying the Englishman found that he had only banknotes in his wallet. He asked the boys to get some change for him, and the two Gipsies made off with one of his notes. He waited and waited, and after half-an-hour he nearly gave up the money for lost, when suddenly the boys came back panting. “ Sorry, sir, to have kept you waiting so long, said the elder of the two, and explained that no less than ten shopkeepers had refused to give them change. believing that the boys had stolen the banknote. Delighted with the happy ending, he rewarded boys accordingly and became a staunch champion of the Gipsies trustworthiness. A few days after this incident he had the courage of his convictions and staked a wager on it. And, believe it or not, he won the bet.

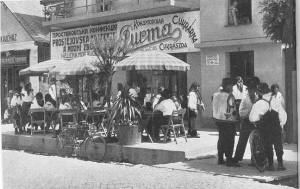

The tragedy of the Gipsies is that they are outcasts in every organised society. Our Englishman found honesty among them perhaps because he spoke their language and they regarded him as one of themselves ; he was not the typical tourist whom Gipsy children and even adults mob and pester for money. Being outcasts, the Gipsies of Carpatho-Ukraine had little scope for their talents ; but, when given a chance, they did not fare so badly. Their musicians, a kind of Gipsy aristocracy who did not mix with the two lower classes, used to be famous for generations and were in demand everywhere in South Eastern Europe, performing at the best cafés and hotels. Under the Czechoslovak regime some Gipsies availed themselves of the educational facilities placed at their disposal, and in 1938 three Gipsies were known to have graduated from a teachers’ college. Other young Gipsies who had been given the opportunity of learning a trade became skilled blacksmiths or stone-masons. With more such outlets the Gipsies might gradually have ceased to be an irresponsible, restless and unreliable clan.

In the period between the two wars an attempt was made by the authorities to organise the Carpatho-Ukrainian Gipsies as a political group. Prominent members of the Gipsy community were put up as candidates for the municipal election. and intensive propaganda was made among the Gipsies to induce them to vote for their own party. Every-thing seemed to be going well; the Gipsy voters accepted the bribes offered by the police official who was one of the party organisers, and promised to cast their votes in favour of their kinsmen. But when it came to the voting the Gipsy electorate thought better of it and left their party in the lurch. The idea of making the Gipsies politically conscious had to be abandoned.

Yet, strange though it may seem, the Gipsies cherished a political Utopia of their own. Like the proverbial hungry man who dreams of opulent feasts, they dreamt of a tree Gipsy country which would be a paradise on earth.

In their impulsive way they were inclined to translate their hopes and dreams into reality and readily believed anything that conformed to their wishful thinking. One day, the Gipsy community was greatly stirred by a rumour that an independent Gipsy State had been established in which every member of the Romany race was a fully fledged citizen. Nobody was able to say precisely where this country was ; but everyone seemed to know that in this promised land no Gipsies were despised, that they were not hunted by policemen, that they were not oppressed.

The rumour spread like wildfire, and the authorities were pestered with inquiries and requests for passports and visas. The passports were never issued, but the hope did not die. As had happened so often in the many centuries of their cursed and hunted existence, the Gipsies had no doubt that, once more, they had been cheated of their claim and right to happiness. But somewhere in their minds there lingered the belief that their promised land did exist. And one day, so they hoped, they would live happily in their Arcadia, where they would be masters in their own house, with plenty of money for everybody and no work, and where roast chickens would fly straight into their Open mouths. And there they would lie idly basking in the blazing sun, or play their traditional tunes no longer, perhaps, the mournful melodies which reflect their tragic history, but rather the wild and breath-taking strains, expressing all the tire and the passion of their effervescent blood.

The rumour spread like wildfire, and the authorities were pestered with inquiries and requests for passports and visas. The passports were never issued, but the hope did not die. As had happened so often in the many centuries of their cursed and hunted existence, the Gipsies had no doubt that, once more, they had been cheated of their claim and right to happiness. But somewhere in their minds there lingered the belief that their promised land did exist. And one day, so they hoped, they would live happily in their Arcadia, where they would be masters in their own house, with plenty of money for everybody and no work, and where roast chickens would fly straight into their Open mouths. And there they would lie idly basking in the blazing sun, or play their traditional tunes no longer, perhaps, the mournful melodies which reflect their tragic history, but rather the wild and breath-taking strains, expressing all the tire and the passion of their effervescent blood.

Their dream ‘was not destined to come true in this world. The self-styled master race had no use for pariahs, and so, during the war, practically the whole Romany community in Carpatho-Ukraine was wiped out.