| Slovakia Genealogy Research Strategies | ||||||

| Home | Strategy | Place Names | Churches | Census | History | Culture |

| TOOLBOX | Contents | Settlements | Maps | FHL Resources | Military | Correspondence |

| Library | Search | Dukla Pass | ||||

INS/USCIS Historical Essays

Who's Got What | USCIS Immigration Service Petitions | EIDB Research Strategies

In the course of site reorganization, the U.S. Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services has not reinstated several very illustrative and important documents relative to genealogy research. Until such time that USCIS reinstates this material, I have reprinted it here for reference. In some cases images were unable to be retrieved and are so noted.

The most important document refutes the old urban legend "They changed his name at Ellis Island". This is far from the truth and the USCIS/INS states as much.

Contents

- American Names / Declaring Independence

- Changing Immigrant Names

- Alien Registration Records, 1940-1944

- Glossary of Passenger List Annotations

- Declaration of Intention

- Petition for Naturalization

- Certificate of Naturalization

- Citizenship Documents issued by INS since 1906

- "Any woman who is now or may hereafter be married . . ." (Women and Naturalization, ca. 1802-1940 By Marian L. Smith )

- Visa Files, 1924-1944

- Why Isn't the Green Card Green?

American Names / Declaring Independence

by Marian L. Smith, INS Historian

Note the following story, which is a perfect specimen of a peculiar quality of the American mind, one bearing no small relation to Independence Day:

I have a friend who tells the story of her ancestor coming from one of the Slavic countries and he, of course, could speak no English. At Ellis Island when he was being processed and any question was asked, he would nod his head and smile. Since all he did was smile when they asked his name, the clerk wrote down 'Smiley' for his surname. That was the family surname from then on.

Whenever I see one of these "name change" stories, I'm reminded of the beautiful creation stories of the Native Americans, "How the Bear Lost his Tail," for example. These stories contain an important truth. They help us understand our world. But we are foolish if we take each one literally, without further investigation. The idea that all bears have short tails because an ancient bear's tail was frozen into the ice is not a very scientific explanation. Similarly, the idea that an entire family's name was changed by one clerk--especially one at Ellis Island--is seldom supported by historical research and analysis.

American name change stories tend to be apocryphal, that is, they developed later to explain events shrouded in the mist of time. Given the facts of US immigration procedures at Ellis Island, the above story becomes suspect. In the story, the immigrant arrives at Ellis Island and a record is then created by someone who cannot communicate with the immigrant, and so assigns the immigrant a descriptive name. In fact, passenger lists were not created at Ellis Island. They were created abroad, beginning close to the immigrant's home, when the immigrant purchased his ticket. It is unlikely that anyone at the local steamship office was unable to communicate with this man. His name was most likely recorded with a high degree of accuracy at that time.

It is true that immigrant names were mangled in the process. The first ticket clerk may have misspelled the name (assuming there was a "correct spelling"--a big assumption). If the immigrant made several connections in his journey, several records might be created at each juncture. Every transcription of his information afforded an opportunity to misspell or alter his name. Thus the more direct the immigrant's route to his destination, the less likely his name changed in any way.

The report that the clerk "wrote down" the immigrants surname is suspect. During immigration inspection at Ellis Island, the immigrant confronted an inspector who had a passenger list already created abroad. That inspector operated under rules and regulations ordering that he was not to change the or identifying information found for any immigrant UNLESS requested by the immigrant, and unless inspection demonstrated the original information was in error.

Furthermore, it is nearly impossible that no one could communicate with the immigrant. One third of all immigrant inspectors at Ellis Island early this century were themselves foreign-born, and all immigrant inspectors spoke an of three languages. They were assigned to inspect immigrant groups based on the languages they spoke. If the inspector could not communicate, Ellis Island employed an army of interpreters full time, and would call in temporary interpreters under contract to translate for immigrants speaking the most obscure tongues.

Despite these facts, the Ellis-Island-name-change-story (or Castle Garden, or earlier versions of the same story) is as American as apple pie (and probably as common in Canada).

Why?

The explanation lies in ideas as simple as language and cultural differences, and as complex as the root of American culture. We all know names have been Anglicized in America (even the word "Anglicized" has been Americanized!). As any kindergartener learns, we live in a world where people ask our name then write it down without asking us how to spell or pronounce that name. Immigrants in America were typically asked their name and entered in official records by those who had "made it" in America and thus were already English-speaking (i.e., teachers, landlords, employers, judges etc.). The fact that those with the power to create official records were English-speaking explains much about small changes, over time, in the spelling of certain names.

Many immigrants welcomed this change. Anyone from Eastern Europe, with a name LONG on consonants and short on vowels, learned that his name often got in the way of a job interview or became the subject of ridicule at his child's school. Any change that might smooth their way to the American dream was seen as a step in the right direction. Perhaps this was the case with Mr. Smiley. It was the case of another family from Russia, named Smiloff or Smilikoff, who emigrated to Canada at the turn of the century. By the time their son immigrated to the US in 1911, his name had become Smiley. But some name changes are not so easy to trace. Rather than a different spelling of the same-sounding name, an entirely new name was adopted. These are the most American stories of all.

"Who is this new man, this American?" asked de Toqueville. He was Adam in the Garden, man beginning again, leaving all the history and heartbreak of the Old World behind. The idea that what made America unique was the opportunity for man to live in a state of nature, a society of farmers whose perception of Truth is unfettered by ancient social and political conventions lies at the base of Jeffersonian democratic theory. The New World became a place for mankind to begin again, a place where every man can be re-born and re-create himself. In such circumstances, the adoption of a new name is not surprising. Nor is it surprising in the cases of immigrants who came to America to abandon a wife and family or to escape conscription in a European army. There were all kinds of reasons, political and practical, to take a new name.

A newspaper in California recently ran the story of a Vietnamese immigrant with a long, Vietnamese name so strange-looking to Anglo eyes. The young man came to this country and began to work and study. He began every day by stopping at a convenience store to buy a "bonus pak" of chewing gum. Chewing all those sticks of gum got him through long days of working several jobs and studying English at night. When he finally naturalized as a US citizen, he requested his name be changed to Don Bonus--the surname taken from the "Bonus Pak" and chosen to signify all his work and effort to become an American. He was a new man.

If not for the newspaper story, we would not understand this name change. Mr. Bonus' naturalization papers would simply record the name change but not the reasons behind it. If he had not naturalized, his Bonus family descendents generations from now would be at quite a loss to explain the origin of their name.

The documentation of name changes during US naturalization procedure have only been required since 1906. Prior to that time, only those immigrants who went to court and had their name officially changed and recorded leave us any record. Congress wrote the requirement in 1906 because of the well-known fact that immigrants DID change their names, and tended to do so within the first 5 years after arrival. Without any record, immigrants and their descendents are left to construct their own explanations of a name change. Often, when asked by grandchildren why they changed their name, old immigrants would say "it was changed at Ellis Island."

People take this literally, as if the clerk at Ellis Island actually wrote down another name. But one should consider another interpretation of "Ellis Island." That immigrant is remembering his initial confrontation with American culture. Ellis Island was not only immigrant processing, it was finding one's way around the city, learning to speak English, getting one's first job or apartment, going to school, and adjusting one's name to a new spelling or pronunciation. All these experiences, for the first few years, were the "Ellis Island experience." When recalling their immigration decades before, many immigrants referred to the entire experience as "Ellis Island."

So, on this day when we celebrate the breaking of our bond with the Old World, let us welcome Mr. Smiley and all the new immigrants who will, in the next few years as they become Americans, make changes to their name which will confuse and confound their descendents for generations to come.

Changing Immigrant Names

"We know from experience that records of entry of many aliens into the United States contain assumed or incorrect names and other errors." From INS Operations Instruction 500.1 I, Legality of entry where record contains erroneous name or other errors, December 24, 1952.

Among the reasons for the "incorrect" names were the immigrant's using:

- A [fictitious] name

- The name of another person

- The true name in a misspelled form

- The surname of the stepfather instead of the natural father

- The surname of a putative father in the case of an illegitimate child

- A nickname

- The name used because of foreign custom, such as the given name of the father (with or without prefix or suffix) for the surname, the name of the farm, or some other name formulated by foreign custom

- The maiden name instead of the married name

- The maiden name of the mother instead of the father's surname

Name Change Stories

When an immigrant's new name no longer matched that shown on their official immigration record (ship passenger list), he or she might face difficulties voting, in legal proceedings, or naturalization. Letters from immigrants to the INS illustrate this problem.

All the letters were found among INS records now at the National Archives (Record Group 85) in Washington, DC, specifically Administrative Records relating to Naturalization, 1906-1944 (Entry 26).

File 106968/309

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DCDetroit, Mich.

November 23, 1915

Hon. Richard K. Campbell

Commissioner of Naturalization

Department of Labor

Washington, D.C.My dear Mr. Campbell:

My Secretary is a teacher in a class of the Wiemann Settlement in which Sam Amber is a pupil. Mr. Amber is twenty-three years of age and desires to make application for his first citizenship papers. He finds himself handicapped, however, by the fact that when he landed in New York September 29, 1912, he gave his name as Salim Bahash. He was born in Syria and his father's name is Charles Amber. I would be very glad if you will kindly advise me of any steps that Amber may take to correct the record and permit of his application for citizenship.

Thanking you for your attention, and with best wishes, I am

Very sincerely yours,

[signed]???

File 10088/364

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DCColumbia, Pa., May 15, 1916

Commissioner of Naturalization

U.S. Department of Labor

Washington, D.C.Dear Sir:

Joseph Eichhorn, a resident of Columbia, Pa., has applied to me for information as to the proper course of procedure, the following being the facts:

Mr. Eichhorn emigrated to the United States from Richelsdorf, Germany, and arrived at the port of Baltimore, Maryland, September 6, 1893. He proceeded thence to West Virginia and made his home in Marrion County, that State, for some years. While there he was advised to drop the "Eich" from his name to facilitate the pronunciation thereof and on May 21, 1902, he was naturalized "at an Intermediate Court held in and for the County of Marrion, at the Court House thereof, May 21, 1902, as Joseph Horn." He subsequently moved to this city and has resided here for 10 years or more. He is desirous of restoring the "Eich" to his name and to have same appear in his Certificate of Naturalization. Can this be done? If so I would appreciate the kindness of directions in the premises.

Very truly yours,

[signed]

Clem W. B-----

File 106968/339

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DC## Schwarts St.

Edwardsville, Ill. March 8, 1917Mr. Rodenberg

East St. Louis, Ill.Dear Sir:

I tried to obtain naturalization papers but could not becuase I did not apply for them under my right name. In Russia I was called Simhe Kohnovalsky but when I arrived in the United States I was told that in English I should call myself Sam Cohn and have been calling myself Sam Cohn for fourteen years and am known by that name. There is no other reason for my boing by a different name that the reason stated above.

I have applied for naturalization papers a second time and in the first papers have given my real name Simhe Kohnovalsky but I would like to have my name changed to Sam Cohn, the name by which I am known, so I am writing to you to ask you how I can have my name changed for the second papers.

I arrived in United States in Brooklyn, New York, July 4, 1903. I was born in Balistok, Russia. The port from which I sailed was Liverpool, England, on the 23rd day of June. I resided in New York City N.Y. for three years, in Clinton, Ill., one year, in St. Louis Mo. one year and since nineteen hundred and eight (1908) I have lived in Edwardsville, Ill.

I have good witnesses for my naturalization papers. I am working in the N.O. Nelson Manufacturing Co.

Please answer and let me know how I can have my name changed on my second papers to Sam Cohn.

Thanking you very much for the trouble, I remain,

Yours respectfully,

Sam CohnHow Diamond Became Cohen

File 106968/300

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DCAugust 27, 1915

Secretary of State

Washington, DCDear Sir:

A client of ours by the name of Louis Diamond, came to this country some twenty odd years ago and resided, at that time, with his brothers in Chicago, Illinois. These brothers, for some reason or other, had changed their names to Cohen, and our client, being then a minor, also adopted the name of Cohen.

On the 8th day of October, 1900, he was given his final certificate of naturalization in the Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois, under the name of Louis Cohen. He has since removed to New York City, and being known by all his friends and relatives as Louis Diamond, he discarded the name Cohen and assumed his real true name.

He cannot, however, vote on account of the facts as above stated, and is desirous of having his naturalization papers changed so that his real and correct name should appear therein.

We would, therefor, thank you to kindly advise, what, if anything, can be done in the matter, and thanking you for an early reply.

Very truly yours,

[signed]

Kaplan & Kosman

File 106968/310

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DC11/25/15

Sirs:

On November 22d I became a citizen of the United States of America under the name of Wolf Zakotsky. I have one son Jack going to High School and another son Abraham works. Their name is Shukowsky which is my right name. Since their name is different than mine, which excludes them from voting on my papers (as sons) I would like to change my name so that all the members of the family have one name. Kindly oblige me by answering as to the best thing to do in order to have the family under one name.

Yours respectfully,

Wolf Zakotsky

1415 Stebbins Ave.

Bronx, N.Y.

(NOTE: Curiously, it seems Mr. Zakotsky/Shukowsky did not take advantage of the name-change provision afforded during naturalization procedures since 1906. Rather, three days after his opportunity to choose the name which would appear on his certificate, he writes inquiring about name change procedure.)

File 106968/323

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DC[April, 1916]

Gentlemen;

One John M. Asszony, a native of Hungary was naturalized at Trenton, New Jersey on September 21, 1896. He has since died. Shortly after he was naturalized he sent for his family who were in Hungary. One of the family was a boy Joseph M. Asszony, who at the time he came here was 13 years of age. When his father died he took up his fathers papers and found that the papers had been issued in the name of John Miazaroz. The only plausible reason for this mistake perhaps was the fact that the applicant was a foreigner and hard to understand.

The son Joseph M. who resides in this city would like to have this corrected so that he may vote under his fathers papers and under his own proper name, which under the present premises is hardly possible. If there is any possible way of remedying this, I would be more than glad to have it.

. . . It will be more than possible for me to furnish affidavits to prove my contention.

Respectfully yours,

[signed]

[I.?] Jean Rosenberg

File 106968/169

Entry 26, RG 85, National Archives, Washington, DCMarch 19, 1912

Bureau of Naturalization

Washington, DCGentlemen:

Please let me know what you require to be the legal practice in a case of this kind.

A man left the other side and for some reason of his own, traveled in coming over here under a different name. When he reached this country he resumed his correct name, and declared his intention and secured his first papers under his correct name. He now would like to find out whether he can make out his application for naturalization papers in the proper form and not say anything with reference to his coming in under the other name, or whether you require him to file an affidavit at the time he files his second application, stating the true facts.

A prompt answer will greatly oblige.

Respectfully yours,

[signed]

Harry J. Weiner

Alien Registration Records, 1940-1944

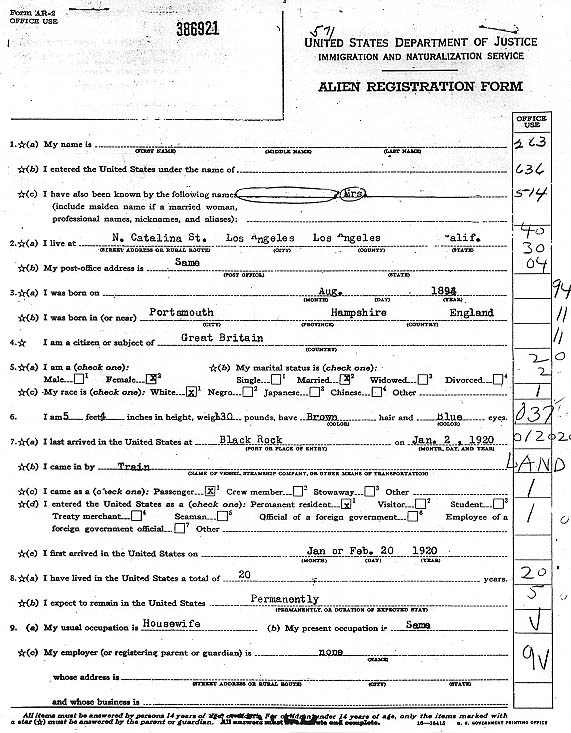

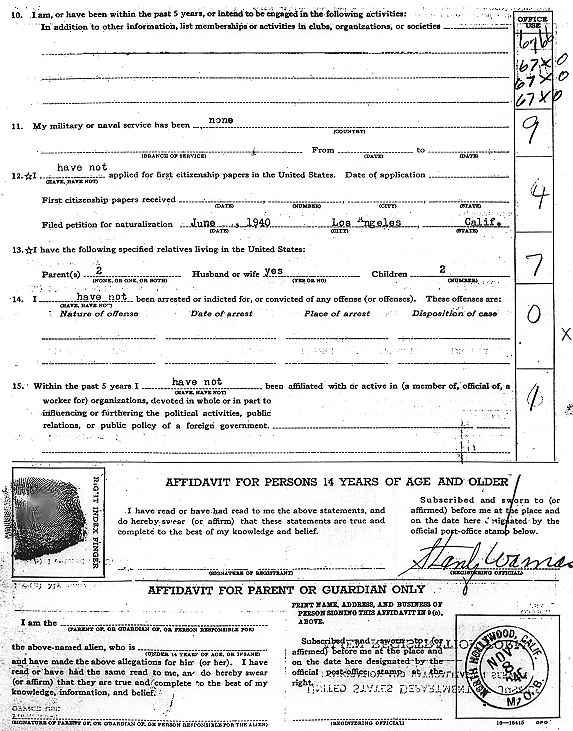

In response to distant threats of war, the United States launched the Alien Registration Program in July of 1940. Pursuant to the Alien Registration Act of that year, every alien resident in the United States had to register at their local Post Office while aliens entering the country registered as they applied for admission. Alien Registration requirements applied to all aliens over the age of fourteen, regardless of nationality and regardless of immigration status.

|

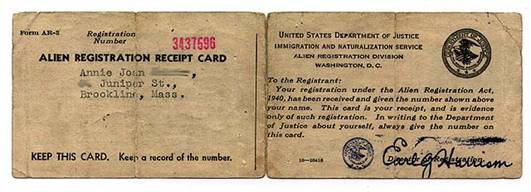

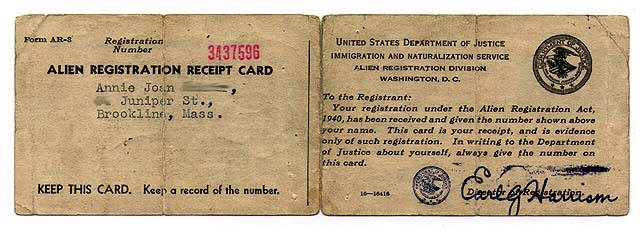

Most resident aliens registered at a Post Office between July and December, 1940. To register, aliens were fingerprinted and filled out a two-page form. Perforations attached an additional card form (the AR-3) to the registration form. Each set of forms were serially numbered with a new development in Immigration and Naturalization Service recordkeeping--the Alien Registration Number. Registration officials forwarded completed forms to the INS for statistical coding, indexing, and filing. Once the AR-2 had been processed, the AR-3, or Alien Registration Receipt Card, was torn off and mailed to the registered alien. The alien then carried the Alien Registration Receipt Card to show compliance with the law.

Many millions of aliens who registered in 1940 had long been resident in the United States and remained here ever after. In some cases, a 1940 Alien Registration is the only INS document concerning such individuals. Early registrations (c. July 1940-April 1944/A-numbers below 12,000,000) are on microfilm in INS custody, searchable by name, date of birth, and place of birth. These records are subject to the Freedom of Information Act/Privacy Act.

Alien Registration Form (AR-2)

Information included on the Alien Registration Form (AR-2):

Name

Name used upon entry to the United States

Other names used (maiden names, nicknames, aliases)

Residence Address

Post Office Address

Date of Birth (month, day, year)

Place of Birth (city, province, country)

Citizenship

Sex

Marital Status (single, married, widowed, divorced)

Race (White, Negro, Japanese, Chinese, Other)

Physical Description (height, weight, hair and eye color)

Date, Port and Vessel/Carrier of Last Arrival in the US

Arrived as: Passenger, Crew member, Stowaway, Other

Class of Admission: Permanent Resident, Visitor, Student,

Treaty Merchant, Seaman, Official of a Foreign Government,

Employee of a Government Official, Other

Date of First Arrival in the US

Number of Years in the US

Usual Occupation

Present Occupation

Employer (or parent or guardian)

Employer's Address

Employer's type of business

Activities and/or membership in clubs, organizations, societies

Military Service: Country, Branch, Dates of Service

Date, Number, City, and State of Declaration of Intention

Date, City, and State of Filed Petition for Naturalization

Number of Relatives living in US (Parents, Spouse, Children)

Arrests (Date, Place, Disposition of Case)

Whether worked for a foreign government in past 5 years

Signature

Fingerprint

AR-2 FRONT

AR-2 BACK

|

AR-3, Alien Registration Card

Alien Registration Receipt Card, issued to a registered alien to demonstrate compliance with the Alien Registration Act of 1940

For more information: Brief Overview of the World War II Enemy Alien Control Program (U.S. National Archives)

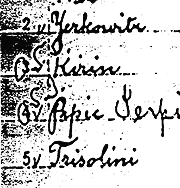

Glossary of Passenger List Annotations

INS did not create ship passenger lists. The forms were completed by steamship companies, who then submitted the forms to the government. In some cases immigration officials annotated the lists to clarify or correct information. In other cases immigration officials later added information to the records as a cross-reference to certain naturalization papers.

Annotations made at time of arrival:

Annotation | Meaning |

|

| "X" at far left, before or in name column = Subject was temporarily detained, see list of detained aliens at end of manifest. |

|

| "S.I." or "B.S.I." at far left, before name = Subject was held for Board of Special Inquiry hearing, see list of aliens held for Special Inquiry at end of manifest. |

| "USB" = US-Born, sometimes found on records of returning citizens. |

| "USC" = United States Citizen, sometimes found on records of returning citizens. |

|

| C-###### = Naturalization certificate number, sometimes found on records of returning citizens. |

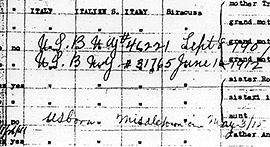

Annotations made after arrival:

Annotation | Meaning |

| "435/621" (or numbers in similar form) with no date given = NY file number (file does not survive). Indicates early verification/record check. |

|

| "432731/435765" (or similar format) = Subject was a permanent resident, returning from a visit abroad with a Reentry Permit. |

| Number in Occupation column (ex: 11-54678 or 2-x-237694) = Verification for naturalization purposes, usually after 1926. First number is naturalization district number, second is either application number or the Certificate of Arrival number. An "x" dividing the number indicates no fee was required for the Certificate of Arrival. Indicates activity in response to filing of a Declaration of Intention or Petition for Naturalization. |

|

| "C/A or c/a" = Certificate of Arrival." Indicates activity in response to filing of a Declaration of Intention or Petition for Naturalization. |

| "V/L or v/l" = Verification of Landing. Indicates verification/record check. |

| "404" or "505" = Verification form used to transmit manifest information to requesting INS office, thus indicating a verification/record check. |

|

| Name (only) crossed out with line, or completely x'd out, with another name written in = name officially amended - additional records may survive |

|

| "W/A or w/a" = Warrant of arrest, additional records may survive |

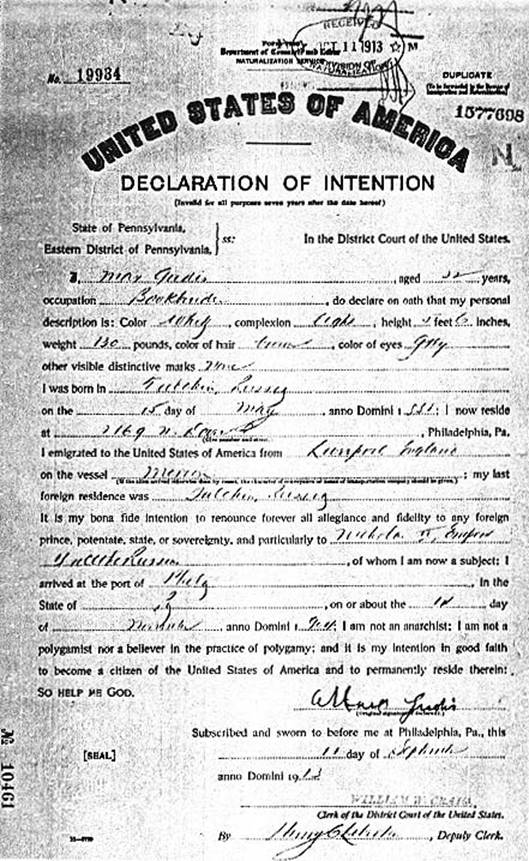

This is an example of a 1913 duplicate Declaration of Intention to become a US Citizen. The original copy was filed among naturalization court records, and the triplicate copy given to the declarant.

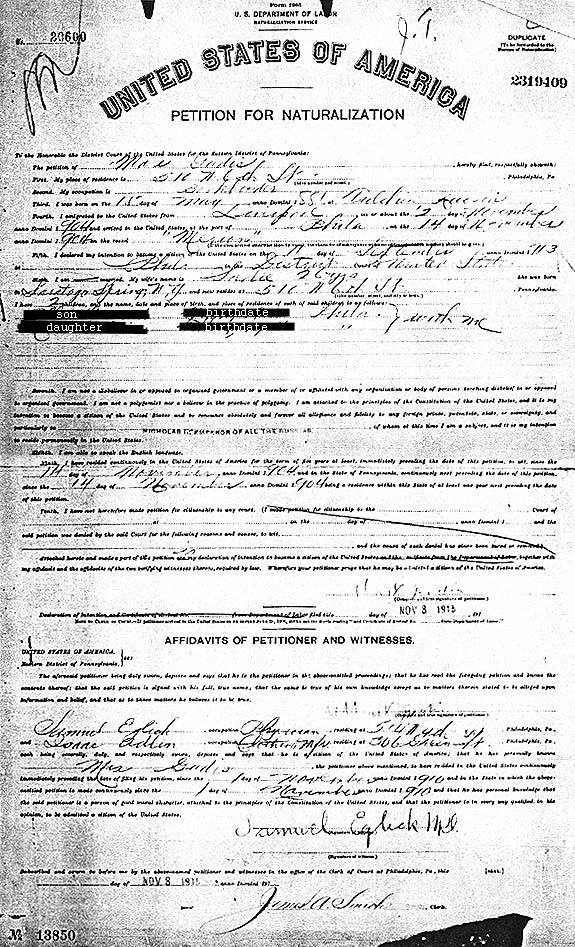

Below is a 1915 duplicate copy of a Petition for Naturalization. The original copy was filed among records of the naturalization court.

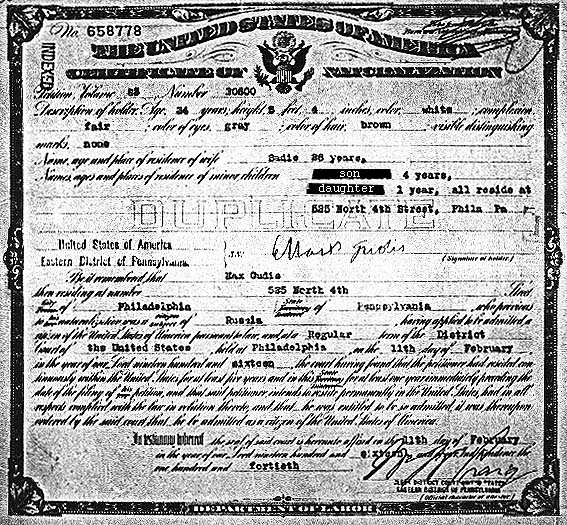

Below is a 1916 Certificate of Naturalization. Beginning in 1929, certificates also included a photograph of the new citizen. Two copies of this certificate were issued by the naturalization court. The original was given to the naturalized citizen as proof of his citizenship. The duplicate was sent to the INS in Washington, D.C.

Citizenship Documents issued by INS since 1906

All records of individuals in the Department custody remain subject to Freedom of Information Act/Privacy Act request | |

"DERIV.A" and/or | Certificates of Citizenship documenting derivative or "acquired" citizenship subsequent to birth (i.e., through the naturalization of a parent). NOT A-Files |

"AA" Files | Certificate of Citizenship documenting derivative or "acquired" citizenship by birth outside the United States or its possessions (i.e., child of US citizen born abroad) |

"OM" Files | Naturalization files related to persons naturalized overseas while members of the Armed Forces of the United States during World War II. All on microfilm. |

"OS" Files | Naturalization files created for persons naturalized outside the United States under the Act of June 30, 1953. |

"B" Files | Certificates of Naturalization or repatriation issued to persons who regained US citizenship, prior to January 13, 1941, either by taking the prescribed oath of renunciation and allegiance before a naturalization court in the US or before a US diplomatic or consular officer abroad, following the loss of citizenship by reason of service in the armed forces of an allied foreign country in WW I or WW II, or by voting in a foreign political election during WW II. |

"D" Files | Certificates of Naturalization or repatriation issued to persons who regained US citizenship, on or after January 13, 1941, either by taking the prescribed oath of renunciation and allegiance before a naturalization court in the US or before a US diplomatic or consular officer abroad, following the loss of citizenship by reason of service in the armed forces of an allied foreign country in WW I or WW II, or by voting in a foreign political election during WW II. |

"3904/-" Files | Containing applications to resume citizenship by persons who lost citizenship as described under "B" and "D" files above, but who never applied for a certificate and for whom no prior certificate file exists. |

"OL" Files | "Old Law" Naturalization Certificates issued by INS to replace naturalization certificates which were lost, destroyed, or mutilated, where the original naturalization certificate was granted under the procedure in effect prior to the Act of June 29, 1906 (which became effective September 27, 1906). |

"15/-" Files | Files relating to persons expatriated prior to 1945. Files in National Archives I, Washington, DC (RG 85, Entry 26). |

"24/-" Files | Files relating to persons expatriated prior to 1945. Files in National Archives I, Washington, DC (RG 85, Entry 26). |

"72/'" Files | Files relating to persons expatriated prior to 1945. Files in National Archives I, Washington, DC (RG 85, Entry 26). |

"129/-" Files | Files documenting the repatriation of women who lost US citizenship by marriage to an alien prior to 1922, and who resumed US citizenship under the Act of June 25, 1936. All on microfilm. |

Prologue Magazine

Prologue Magazine Summer 1998

Summer 1998, Vol. 30, No. 2

Women and Naturalization, ca. 1802-1940

By Marian L. Smith

| In general, immigrant women, such as these arrivals at Ellis Island, have always had the right to become U.S. citizens, but a succession of laws in the nineteenth century worked to keep certain women out of the naturalization process. (NARA, 90-G-125-3) |

The fact that women are not equally represented among the nation's early naturalization records often surprises researchers. Those who assume naturalization practice and procedure have always been as they are today may spend valuable time searching for a nonexistent record. At the same time, many genealogists do find naturalization records for women. The resulting confusion about this subject generates a demand for clear, simple instructions by which to guide research. Unfortunately, the only rule one can apply to all U.S. naturalization records--certainly all those prior to September 1906--is that there was no rule.(1)

There were certain legal and social provisions, however, governing which women did and did not go to court to naturalize. In general, immigrant women have always had the right to become U.S. citizens, but not every court honored that right. Since the mid-nineteenth century a succession of laws worked to keep certain women out of naturalization records, either by granting them derivative citizenship or barring their naturalization altogether. It is this variety of laws covering the history of women's naturalization, as well as different courts' varying interpretation of those laws, that help explain whether a naturalization record exists for any given immigrant woman.

While original U.S. nationality legislation of 1790, 1795, and 1802 limited naturalization eligibility to "free white persons," it did not limit eligibility by sex. But as early as 1804 the law began to draw distinctions regarding married women in naturalization law. Since that date, and until 1934, when a man filed a declaration of intention to become a citizen but died prior to naturalization, his widow and minor children were "considered as citizens of the United States" if they/she appeared in court and took the oath of allegiance and renunciation.(2) Thus, among naturalization court records, one could find a record of a woman taking the oath, but find no corresponding declaration for her, and perhaps no petition.

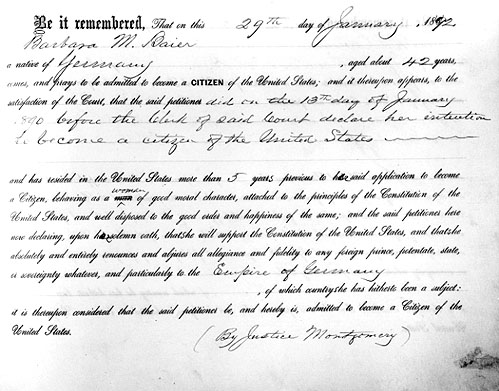

| Barbara M. Baier applied for citizenship in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on January 29, 1892. The clerk had to alter the text to "a woman of good moral character." (NARA, Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21) |

Unless a woman was single or widowed, she had few reasons to naturalize prior to the twentieth century. Women, foreign-born or native, could not vote. Until the mid-nineteenth century, women typically did not hold property or appear as "persons" before the law. Under these circumstances, only widows and spinsters would be expected to seek the protections U.S. citizenship might afford. One might also remember that naturalization involved the payment of court fees. Without any tangible benefit resulting from a woman's naturalization, it is doubtful that many women or their husbands considered the fees to be money well spent.

New laws of the mid-1800s opened an era when a woman's ability to naturalize became dependent upon her marital status. The act of February 10, 1855, was designed to benefit immigrant women. Under that act, "[a]ny woman who is now or may hereafter be married to a citizen of the United States, and who might herself be lawfully naturalized, shall be deemed a citizen." Thus alien women generally became U.S. citizens by marriage to a U.S. citizen or through an alien husband's naturalization. The only women who did not derive citizenship by marriage under this law were those racially ineligible for naturalization and, since 1917, those women whose marriage to a U.S. citizen occurred suspiciously soon after her arrest for prostitution. The connection between an immigrant woman's nationality and that of her husband convinced many judges that unless the husband of an alien couple became naturalized, the wife could not become a citizen. While one will find some courts that naturalized the wives of aliens, until 1922 the courts generally held that the alien wife of an alien husband could not herself be naturalized.(3)

In innumerable cases under the 1855 law, an immigrant woman instantly became a U.S. citizen at the moment a judge's order naturalized her immigrant husband. If her husband naturalized prior to September 27, 1906, the woman may or may not be mentioned on the record which actually granted her citizenship. Her only proof of U.S. citizenship would be a combination of the marriage certificate and her husband's naturalization record. Prior to 1922, this provision applied to women regardless of their place of residence. Thus if a woman's husband left their home abroad to seek work in America, became a naturalized citizen, then sent for her to join him, that woman might enter the United States for the first time listed as a U.S. citizen.(4)

In other cases, the immigrant woman suddenly became a citizen when she and her U.S. citizen fiance were declared "man and wife." In this case her proof of citizenship was a combination of two documents: the marriage certificate and her husband's birth record or naturalization certificate. If such an alien woman also had minor alien children, they, too, derived U.S. citizenship from the marriage. As minors, they instantly derived citizenship from the "naturalization-by-marriage" of their mother. If the marriage took place abroad, the new wife and her children could enter the United States for the first time as citizens. Again, if these events occurred prior to September 27, 1906, it is doubtful any of the children actually appear in what is, technically, their naturalization record. The lack of any record for those children's naturalization might cause some of them, after reaching the age of majority, to go to naturalization court and become citizens again.

Just as alien women gained U.S. citizenship by marriage, U.S.-born women often gained foreign nationality (and thereby lost their U.S. citizenship) by marriage to a foreigner. As the law increasingly linked women's citizenship to that of their husbands, the courts frequently found that U.S. citizen women expatriated themselves by marriage to an alien. For many years there was disagreement over whether a woman lost her U.S. citizenship simply by virtue of the marriage, or whether she had to actually leave the United States and take up residence with her husband abroad. Eventually it was decided that between 1866 and 1907 no woman lost her U.S. citizenship by marriage to an alien unless she left the United States. Yet this decision was probably of little comfort to some women who, resident in the United States since birth, had been unfairly treated as aliens since their marriages to noncitizens.(5)

By the late nineteenth century, marital status was the primary factor determining a woman's ability to naturalize. But other factors might have influenced a judge's decision to grant or deny a woman's naturalization petition. Some judges seemed unaware of legal naturalization requirements and regularly granted citizenship to persons racially ineligible, who had not lived in the United States the requisite five years, or did not display "good moral character." It may be that these judges also granted citizenship to women regardless of their husband's nationality. Women's naturalization records dating from the 1880s and 1890s can be found, for example, among the records of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (Record Group 21), though these records do not indicate the women's marital status.

After 1907, marriage determined a woman's nationality status completely. Under the act of March 2, 1907, all women acquired their husband's nationality upon any marriage occurring after that date. This changed nothing for immigrant women, but U.S.-born citizen women could now lose their citizenship by any marriage to any alien. Most of these women subsequently regained their U.S. citizenship when their husbands naturalized. However, those who married Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, or other men racially ineligible to naturalize forfeited their U.S. citizenship. Similarly, many former U.S. citizen women found themselves married to men who were ineligible to citizenship for some other reason or who simply refused to naturalize. Because the courts held that a husband's nationality would always determine that of the wife, a married woman could not legally file for naturalization.(6)

There were exceptions to the 1907 law's prohibition against the naturalization of married women. Good examples can be found in the West and upper Midwest, where individuals were still filing entries under the Homestead Act in the early twentieth century. Many women filed homestead entries, either while married to aliens or prior to marrying an immigrant. Later, when they petitioned for the citizenship necessary to obtain final deed to the property, some judges granted their petitions despite their marital status. In these cases the judges held that if the government intended to deny the women citizenship it should not have allowed them to file entries with the General Land Office. In other homestead-related cases, the granting of citizenship to women seemed less a matter of principle and more a method, adopted locally, to acquire additional property.(7) Women's inability to naturalize during these years did not prevent them from trying. Many women filed declarations of intention to become citizens and may have even managed to file petitions before being denied. At least one woman's petition came before the court because she did not declare her marital status. Often women had no choice but to file at least a declaration of intent. In some states aliens could not file for divorce or other court proceedings. An alien woman seeking divorce might file the declaration simply to facilitate filing a separate suit.(8) Declarations of intention and petitions filed by women should remain on file with other court naturalization records.

A few women successfully naturalized in these years, but they might have subsequently had their naturalization certificates canceled. Finnish-born Hilma Ruuth, for example, filed her declaration of intention to become a citizen in the U.S. District Court at Minneapolis, Minnesota, on December 1, 1903. In 1910 Hilma married Jaakob Esala, another Finnish immigrant, and in the same year she filed her petition for naturalization with the district court of St. Louis County, at Virginia, Minnesota. Her petition bore her married name, Hilma Esala, and the U.S. Naturalization examiner in St. Paul filed a formal objection to her petition under the 1907 law, which prohibited the naturalization of women married to aliens. The county judge overruled this objection and granted Hilma U.S. citizenship on November 19, 1910. The naturalization examiner responded by passing the case to the U.S. district attorney, who then filed suit in U.S. District Court on January 24, 1911, for cancellation of the certificate. The case was decided on July 11 at the Federal Building in Duluth, where Hilma's citizenship was canceled and she had to surrender her certificate of naturalization.(9) Federal court records of certificate cancellation proceedings are, like federal court naturalization records, found in Record Group 21. Unless there is a name index to the court's records, researchers will need to know the court's specific name (i.e., U.S. District Court, U.S. Circuit Court) and location, the type of case, and case number.

The era when a woman's nationality was determined through that of her husband neared its end when this legal provision began to interfere with men's ability to naturalize. This unforeseen situation arose in and after 1918 when various states began approving an amendment to grant women suffrage (and which became the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1920). Given that women who derived citizenship through a husband's naturalization would now be able to vote, some judges refused to naturalize men whose wives did not meet eligibility requirements, including the ability to speak English. The additional examination of each applicant's wife delayed already crowded court dockets, and some men who were denied citizenship began to complain that it was unfair to let their wives' nationality interfere with their own.(10)

Happily, Congress was at work and on September 22, 1922, passed the Married Women's Act, also known as the Cable Act. This 1922 law finally gave each woman a nationality of her own. No marriage since that date has granted U.S. citizenship to any alien woman nor taken it from any U.S.-born women who married an alien eligible to naturalization.(11) Under the new law women became eligible to naturalize on (almost) the same terms as men. The only difference concerned those women whose husbands had already naturalized. If her husband was a citizen, the wife did not need to file a declaration of intention. She could initiate naturalization proceedings with a petition alone (one-paper naturalization). A woman whose husband remained an alien had to start at the beginning, with a declaration of intention. It is important to note that women who lost citizenship by marriage and regained it under Cable Act naturalization provisions could file in any naturalization court--regardless of her residence.(12)

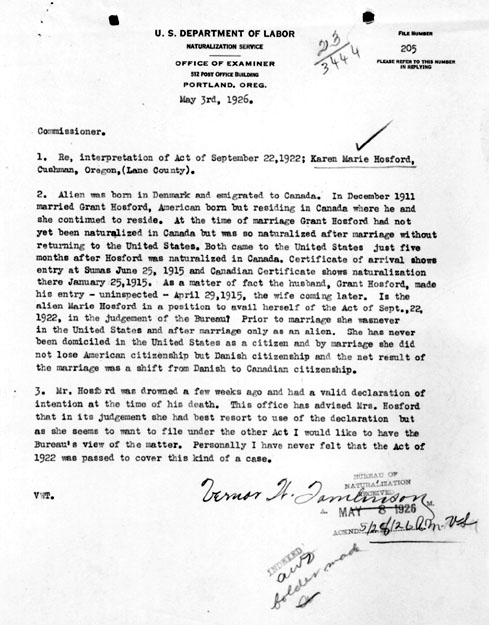

| Karen Marie Hosford had a confusing naturalization problem concerning her husband's declaration of intention and her right to U.S. citizenship. (NARA, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85) |

By this time, confusion over women's citizenship, and how a woman might regain U.S. citizenship, had become common. The case of Karen Marie Hosford is a good example. She was born in Denmark and immigrated to Canada, where she met and married Grant Hosford in 1911. He was a U.S. citizen, and under U.S. law Karen became a U.S. citizen through their marriage. Then Grant naturalized as a Canadian citizen in 1915, and Karen, too, thereby lost her U.S. citizenship. The couple soon migrated to the United States. After a few years Grant decided to regain his U.S. citizenship and filed a declaration of intention at his local naturalization court. Unfortunately, Grant died in 1923, not yet naturalized, and left Karen an alien widow. At that point she could petition for naturalization based on his declaration, citing the original 1804 act which gave her that right. But the 1922 act also gave her the option to file her own declaration and begin the naturalization process in her own right.(13)

"Any woman who is now or may hereafter be married . . ."

Women and Naturalization, ca. 1802-1940, Part 2

While it appears foreign-born women did not complain about any remaining link between a woman's naturalization and her husband's, some Naturalization Bureau officials thought any remaining connection was unfair.(14) Clear dissatisfaction was expressed by U.S.-born women who, in many cases, belatedly discovered they had lost their citizenship by marriage prior to September 1922 and now must petition for naturalization if they wished to regain it. After considering that other Americans who expatriated themselves by swearing allegiance to another nation during World War I needed only to take the oath of allegiance in court to restore their U.S. citizenship, U.S. Commissioner of Naturalization Raymond Crist suggested that Congress might create some similar provision for U.S.-born women:

Some women feel that a certain stigma attaches to the need of "naturalization" in the same manner as any lowly immigrant. Women of perhaps Mayflower ancestry, whose forbears fought through the Revolution, and whose family names bear honored and conspicuous places in our history, who are thoroughly American at heart, and who perhaps have never left these shores, but whose act in choosing alien husbands has caused forfeiture of American citizenship, bemoan the stipulation that such as they must sue for naturalization by the ordinary means.(15)

Not until 1936 did Congress comply with Crist's request, and then only for those women who lost U.S. citizenship by marriage between 1907 and 1922 and whose marriage had terminated through death or divorce. If she met this criteria she could file an application with her local naturalization court and resume her citizenship upon taking the oath of allegiance. The application was typically made on Form N-415, Application to Take Oath of Allegiance to the United States, which should be filed in separate volumes from each court's other naturalization records. Some courts, however, interfiled these documents with other petitions. In 1940 Congress allowed all women who lost citizenship by marriage between 1907 and 1922 to repatriate, or resume their citizenship, regardless of their marital status. Since then, any woman who lost U.S. citizenship in those years by marriage to any alien, even if they remained happily married, could resume her citizenship by applying and taking the oath of allegiance.

| In this 1921 photograph, only one women is taking the naturalization class for citizenship. It was not until the following year that women would finally get a nationality of their own and more women would seek to be naturalized. (U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service) |

The subject of women and naturalization was often as confusing to people in the past as it is to researchers today. Not all courts upheld or strictly enforced naturalization requirements. Other misunderstandings arose when naturalization records did not change as rapidly as did naturalization law. For example, after implementation of the Cable Act in 1922, naturalization certificates continued to call for the name of the new citizen's spouse until at least 1929. This was a remnant of the days when women derived nationality from their husbands, and the name inserted on the certificate after 1922 was usually that of the wife. There were subsequently instances where unnaturalized spouses used such certificates as proof of citizenship, even using them to obtain U.S. passports from the Department of State.(16)

Still other misunderstandings arise today because some are unable to fathom that immigrant women may have gained U.S. citizenship by any means other than naturalization. There is a surprising number of elderly women alive today who gained U.S. citizenship by marriage to U.S. citizens prior to 1922. Too often they and their children are sent scrambling to obtain some proof of the woman's citizenship so that she might retain some benefit to which she is entitled. It was not until 1929 that women who gained citizenship through their husband's naturalization after marriage could obtain a "Certificate of Derivative Citizenship" from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). And it was not until 1940 that INS could issue certificates to women who gained citizenship by marriage to a man already a citizen.(17) While not in themselves proof of citizenship for legal purposes, proof of marriage to a U.S. citizen occurring prior to September 22, 1922, and proof of the husband's U.S. citizenship, remain as the foundation for legally documenting a foreign-born woman's citizenship.(18)

Notes

1. For information on the location of federal, state, and local court naturalization records and their availability on microfilm, see Christine Shaefer, Guide to Naturalization Records of the United States (1997). For information about various aspects of naturalization laws and procedures, see John J. Newman, American Naturalization Processes and Procedures, 1790-1985 (1985).

2. Act of March 26, 1804--Widow and Children of Declarant (§ 2168) "shall be considered as citizens of the United States, and shall be entitled to all rights and privileges as such, upon taking the oaths prescribed by law." Repealed by Basic Naturalization Act of June 29, 1906, but continued in section 4(6) of that act. Repealed 1934, but citizenship of those who previously gained citizenship under this provision remained secure. An act of February 24, 1911, allowed the wives of insane declarants to naturalize following the same procedure.

3. Act of Feb. 10, 1855 (§ 1994, rev. § 2172); see In re Rionda, 164 F 368 (1908); United States v. Cohen, 179 F 834 (1910).

4. Sidney Kansas, Citizenship of the United States of America (1936), p. 67.

5. Frederick A. Cleveland, American Citizenship as Distinguished from Alien Status (1927) pp. 65-66.

6. Ibid.; see also Rule 24(k) of the Naturalization Laws and Regulations, Feb. 15, 1917 (1917), p. 33.

7. Report of Robert A. Coleman, Chief Naturalization Examiner, St. Paul, MN, to Richard K. Campbell, Commissioner of Naturalization, Washington, DC, July 1, 1910, p. 3, entry 26, box 1698, file 457177, pt. I, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereinafter RG 85, NARA).

8. Robert A. Coleman, Chief Naturalization Examiner, St. Paul, MN, to Commissioner of Naturalization, Washington, DC, Feb. 2, 1924, entry 26, box 399, file 20/2, RG 85, NARA. See also "Must be Naturalized under Married Surname of Husband," in Kansas, Citizenship of the United States of America, pp. 70-71.

9. INS C-File 154992 (including naturalization records of Hilma Esala, District Court of St. Louis County, at Virginia, MN, Nov. 19, 1910, and court decree of the U.S. Circuit Court, District of Minnesota, Fifth Division, July 25, 1911, and other correspondence).

10. Sundry correspondence relative to courts requiring wife of petitioners to attend court at final hearing, 1919-1922, entry 26, box 1475, file 3929, RG 85, NARA.

11. Until 1931, women still expatriated themselves by marriage to an alien racially ineligible to naturalize.

12. Luella Gettys, The Law of Citizenship in the United States (1936) p. 50.

13. Case of Karen Marie Hosford, entry 26, file 23/3444, RG 85, NARA.

14. Paul Armstrong, Chief Naturalization Examiner, Denver, CO, to Commissioner of Naturalization Raymond Crist, Washington, DC, June 30, 1923, entry 26, box 399, file 20/2, RG 85, NARA.

15. Annual Report of the Commission of Naturalization, 1923, p. 13.

16. Thomas Griffing, District Director of Naturalization, St. Louis, MO, to Commissioner of Naturalization, Apr. 3, 1929, entry 26, box 399, file 20/2, RG 85, NARA.

17. Nora H. Reardon, "Derivative Citizenship of the United States--the Law, Procedure, and Practice in its Determination, and in the Issuance of Documentary Evidence of Such Status." (lecture, INS Course of Study for Members of the Service) Jan. 7, 1943, pp. 14-15.

18. Naturalization Examiner's Guide, Applications for Certificates of Citizenship, Documentary and Other Evidence (INS, Nov. 1, 1964), pp. 8-20 to 8-25 (TM 8-1-70).

Certificates of Derivative Citizenship are issued only by INS, not by the courts. To apply for a certification of citizenship, submit INS Form N-600 to your local district office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government. |

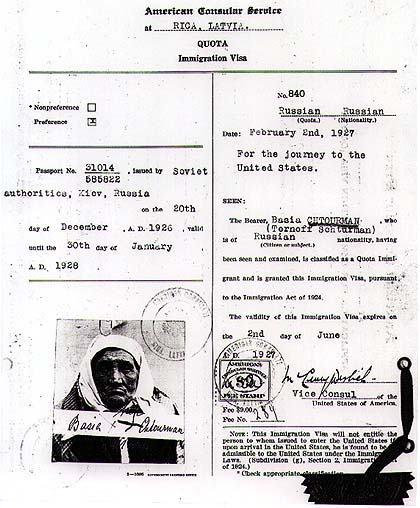

Front of typical visa form, indicating the issuance date and consulate, naming the immigrant, and bearing a photograph.

Inside the unfolded visa application form, below. A long questionnaire compiles all information required by US immigration law, in many ways identical to that found on ship passenger manifests. Visa applications also asked for the names and addresses of both the immigrant's parents as well as all the immigrant's minor children. It also asked for all the immigrant's residential addresses for five full years prior to emigration. A variety of documents and/or vital records may be attached to a visa.

Why Isn't the Green Card Green?

What we know as a "green card" came in a variety of different colors at different times in its history. We still refer to them as "green cards" for the same reason dismissal notices are called "pink slips," sensationalized news is called "yellow journalism," and intended distractions are called "red herrings." In each case, an idea was originally associated with an actual item of the respective color. A Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) alien living in the United States may carry a card that is not green, but refers to it as a "green card." The alien does so because the card bestows benefits, and those benefits came into being at a time when the card was actually green.

AR-3, The Original Green Card

Links to off-site webs will open in a new window. Please disable your pop-up stopper.

Last Update: 15 November 2020 Copyright © 2003-2021, Bill Tarkulich