| Slovakia Genealogy Research Strategies | ||||||

| Home | Strategy | Place Names | Churches | Census | History | Culture |

| TOOLBOX | Contents | Settlements | Maps | FHL Resources | Military | Correspondence |

| Library | Search | Dukla Pass | ||||

Military History - Northeast Slovakia

Military History - Northeast Slovakia

Lecture Notes

“Carpatho-Dukla Operation”

September 8 to October 25, 1944

Bill Tarkulich

COPYRIGHT 2006-2008

The following is an expansion of an presentation I made to the New Jersey

chapter of the Carpatho-Rusyn Society. These are generally the same notes used for the CR-S

presentation in Bridgeport, Connecticut and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I hope you learn a little something here and can contribute with your feedback.

![]()

This piece is neither exhaustive nor complete, I leave that to academics. This piece likely contains certain errors by oversight or incomplete research. These are mine alone. This is simply an introduction, providing more information about this neglected region of the world. In time it will evolve into a more complete story. Your comments and corrections are appreciated.

About the Author:

Bill Tarkulich is of Rusyn/German descent. His paternal grandparents were born in the Slovakia villages of Zboj and Nova Sedlica, Slovakia in the 1880s and emigrated to America in the 1910’s. In the process of researching his ancestors, Bill happened to learn of this battle. He made it a point to visit the battlefield and its monument in 2001. This sparked an intrigue, since so few in the West are even aware of this battle. Bill is not a military historian, but felt compelled to expose this event to English-speaking audiences in a simple form that all can appreciate. He feels that to know one’s ancestry it is imperative that one understand the historical events that surround them and took place on their soil. Thus, Dukla becomes an important event for Rusyn, Slovak and Polish descendants to understand and appreciate.

Introduction

The Battle of Dukla Pass, officially known as the “Carpathian Operation” by the battle commanders is perhaps the largest battle you may never have heard about. It was the largest battle (In terms of casualties) ever fought on Slovakia soil. Casualties were immense, suffering over 138,000 in 50 days. Putting it into perspective:

• Casualties (Killed, Missing and Wounded)

• 138,000 - Dukla Pass in 50 days

• 160,000 - Battle of the Bulge in 40 days

• 200,000 – Battle of Budapest in 47 days

• 400,000 - Battle of Normandy in 80 days

• 1.6 million - Battle of Stalingrad in 150 days

Location

The Dukla pass is located in the Outer West Carpathian Mountains. The Western Carpathian Mountains run east-west serving as a natural and political border for Slovakia, Poland, Czech Republic and Ukraine. The mountains are of generally low altitude, 1,300 to 1,600 feet, with the occasional high peak of 5,600 feet. A considerable portion resembles a hilly plateau. The region as we see it today includes fields and pastureland which were formed centuries ago after the wood was harvested. Until the 1940s sheep grazed in large numbers in these hills. Additionally, the forests served as a significant source of timber for the region.

The Dukla Pass (Dukliansky priesmyk) has for centuries been the lowest and easiest north-south route. The pass has always been a major trade route, connecting eastern Slovakia with southern Poland. It offered traders easy access to the Hungary plains immediately to the south. The regions surrounding Dukla Pass to the north and south have been populated since at least the 1500s by peasant Carpatho-Rusyn inhabitants. The population of the north slopes was inhabited by ethnic Lemko while to the south, Carpatho-Rusyn. On the south slopes of Ukraine these people were known as ethnic Boiko and Hutsul. Shortly following World War II, the Lemko population was forcibly deported and their settlements destroyed by the government of Poland (“Operation Vistula”), being blamed for supporting the partisan operations of pro-Ukrainian nationalists (“UPA”), who wanted their own nation to be formed. Sadly, the Lemko regions of Poland were depopulated for two decades, slowly being re-inhabited by ethnic Poles. The primary activity nowadays is outdoor tourism, principally hiking and camping.

Not the First Time

World War II was not the first time the pass was involved in military operations. During the Hungarian War of Independence in 1849, Russia sent 200,000 soldiers and 584 cannons south through the pass in support of Vienna, effectively crushing the Hungary rebellion. The troops moved through the pass southward to the Hungarian plains, but there was no fighting in the pass itself.

In World War One, two Carpathian passes, Krosno and Dukla, were taken by the Russians in September 1914, much to the embarrassment of the Austria-Hungary Empire. In December, 1914, Dukla pass was re-taken by Austria-Hungary.

What 1938 Wrought

In 1938 Nazi German began its eastward offensive intent on expanding its empire and gaining access to important natural resources. The “anschluss” included Austria and the Bohemia and Moravia lands of Czechoslovakia, which Hitler claimed as rightly Germanic. Czechoslovakia had little choice but to acquiesce to the demands of Hitler. The Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia were annexed into Germany. Germany then permitted Hungary to acquire the easternmost portion of Czechoslovakia, “Carpatho-Ukraine.” The lands taken inlcuded southern fringe borderlands and an eastern slice of Slovakia just to the east of Snina.

In 1939 an independent Slovakia was formed, at Hitler’s urging and by March became a German Protectorate. by 1939 Slovakia became a pathway to Poland and eastward to the USSR for use by the Germans in the expansion.

1939 Invasion of Poland

In September, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. The Dukla Pass was instrumental in this invasion. The Slovakia army participated in the invasion: The First Division “Janosik” (led by General Anton Pulanich), and the Mobile Group “Kolinciak” crossed border on Sept 8 but did not participate in any fighting. Interestingly, 5 years to the day, Slovakia was re-invaded at Dukla pass, beginning the ridding Nazi occupation from the nation.

1939 to 1944

In March, 1939, the Vienna Award allowed Hungary to take possession of the Carpatho-Ukraine section of Czechoslovakia, Hungary forcibly annexed the easternmost section of Slovakia, westward to the outer bounds of the village Snina, Slovakia. In 1940 Hungary formally allied itself with Germany. During the period 1939 to early 1944, things were relatively “quiet” in Slovakia. There had been an initial Jewish pogrom in 1942, deporting many but not all Jews. By 1943 German advances into Russia had been turned around and the Red Army was moving eastward. In general Slovakia remained a relatively safe-haven during this period, free from military operations and further pogroms until 1944.

Fast Forward to 1944

The Red Army's “Operation Bagration” was the westward thrust from June to August 1944, which included the First and Second Ukrainian Fronts, was moving swiftly across Ukraine and Poland.

Defensive Preparations: The Arpad Line

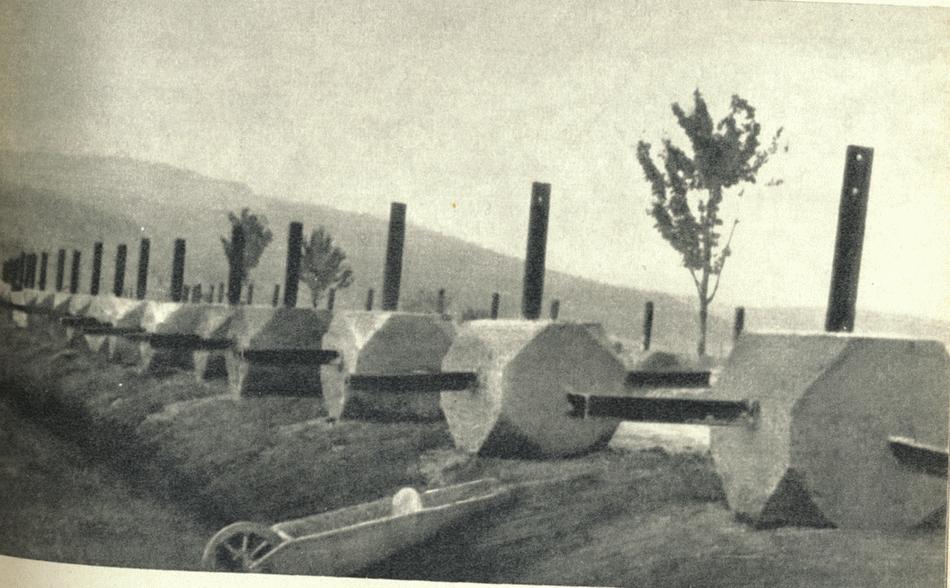

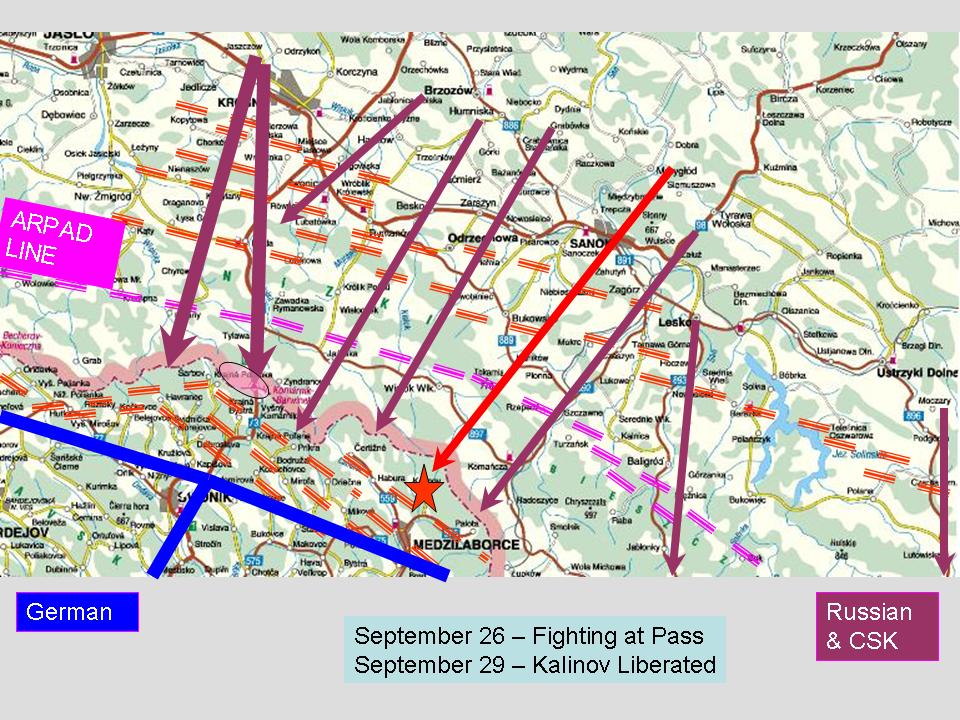

Primary fortifications were built by the Germans, just north of the Carpathian mountains in Poland. Addtional fortifications were built in or near the villages of Mszana, Chyrowa, Tylawa, Olchowiec, Ropianka, Wilsznia, and Smereczne. (Wilsznia), and (Smereczne), all in Poland.

Defense in Hungary and Slovakia

During the first half of 1944, Hungary and Slovakia moved to erect a defensive structure in the Carpathian mountains over a six month period. The Carpathian Mountains were the centerpiece of this defense.

Defensive tactics included:

• Development of the “Arpad Line” – military fortifications in the north foothills of the Carpathians, stretching from present-day Poland, south-eastward through Ukraine. I believe this was the same name used for similar World War One fortifications

• Tank traps, armor, lookout towers and thousands of land mines, wire entanglements in the forests and roads

• The forests were partly cut, with logs dropped specifically to impede travel

• Local citizens conscripted to dig trenches

• Positions along flanking ridges and slopes with fortified bunkers built into the hillside

Defensive Preparations in Poland

While the Dukla Pass itself later became a focal activity, the Poland town of Krosno, about 20 miles north of the pass was an initial strategic target. The Krosno region contained important oil fields which were a source of fuel for Nazi Germany. The aerial bombing of the Krosno region began earlier in order to destroy the source for the Germans. The area was also heavily fortified on the ground by German Troops.

Krosno was converted into a strong point, girded by continuous trenches. Rock houses were fitted as defensive positions, in them machine-gun stations had been placed. Streets were covered with barricades 1.5 meters high, built from the stone and the logs; stone buildings were mined. Approaches to the city were covered by minefields and trenches.

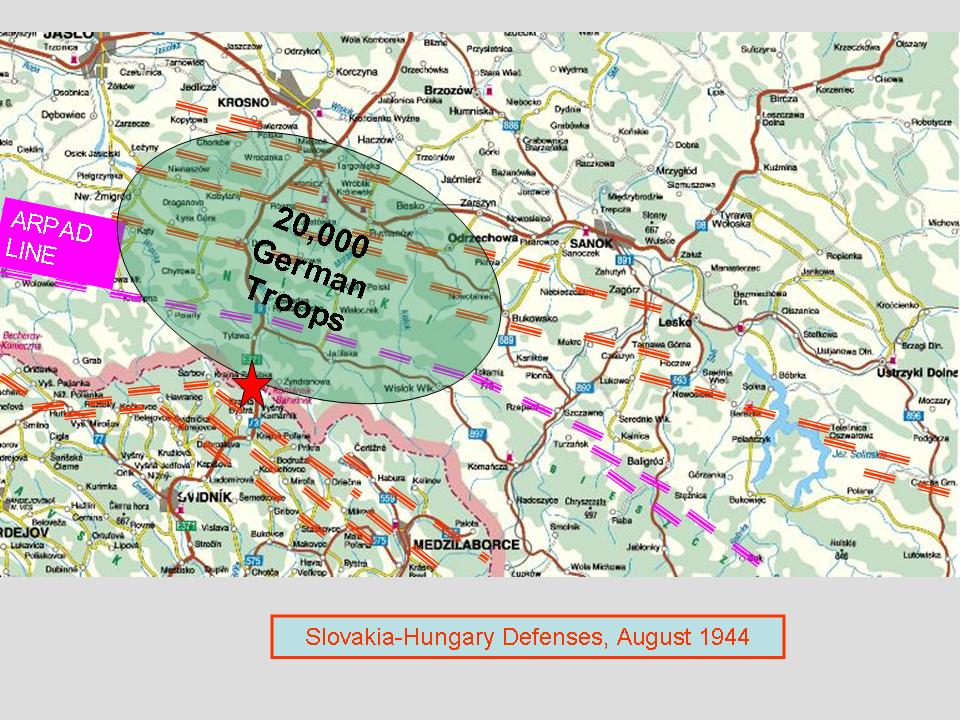

The region from Krosno southward to Carpathian Mountains was held by 20,000 German troops, with 200 artillery pieces. There were 3 German infantry divisions and 2 German Corps. The Germans recognized the importance of this pass and aimed to defend it. In this region, three levels of defensive lines constructed, each about 5 miles apart, positioned north of the mountains and running parallel to the mountains.

General Ivan S. Konev, Soviet commander of the First Ukrainian front, writes in his memoirs that German Defense in the Krosno-Dukla area included the 545th, 208th and 68th infantry divisions, (part of the 11th army corps SS), 17th armies and 24th Guards of the armored corps, 1st tank army, Commanded by General Kheynritsi, of the Soviet high command reserve, 1004th Guards, the 611th Guards regiment company and the 96th infantry division.

The Soviet Plan

By August 1944, the Slovak National Uprising was well underway. The Soviets had many intelligence resources in Slovakia, most of them being Slovak partisans, who would slip through the mountainous borders in Ukraine to facilitate communications with the coordinated uprising, as well as to provide enemy troop location and information. They became an important element in the Stavka (Soviet Army High Command) decision to assist the uprising.

During the period of 1943 and 1944 the Soviet Union had provided considerable assistance to the partisans, both in terms of arms smuggled and airlifted in, as well as key leadership.

While the partisan had planned a coordinated uprising for a later date (to be known as the Slovak National Uprising or Slovenské národné povstanie / SNP), the activities of the partisans escalated to such a level that by August the uprising had occurred spontaneously. On August 29th, the uprising began in Banska Bystrica, becoming the uprising's focal point.

The original Stavka battle plan was for the First Ukrainian front to continue its westward advance through Poland towards Berlin, and the Second Ukrainian front to advance towards Budapest and Vienna. Fighting in the mountainous regions was to be avoided, being too difficult and too slow. There was no plan to attack across any of the mountain passes.

Decision to attack through Dukla: General Konev writes in his memoirs that the decision to alter their plan and assist the SNP was made five days after the uprising began. The decision was made for four reasons:

- To support the uprising

- To respond to the inability of Fourth Ukrainian front to move decisively west across the Carpathian Mountains in Ukraine

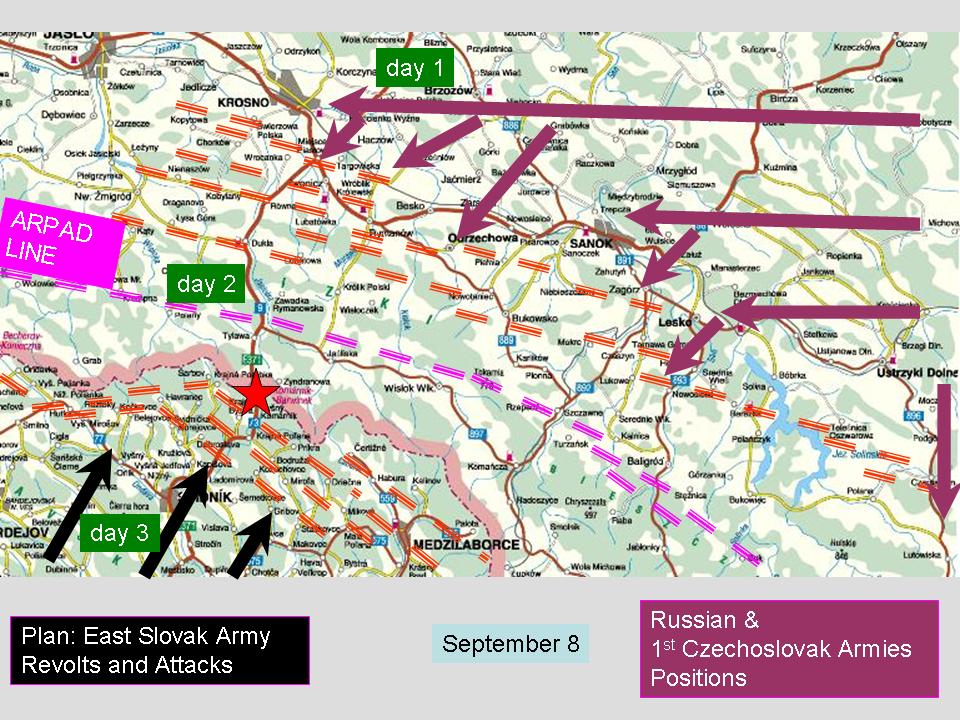

- The expectation that the East Slovak Army Corps of 32,000 troops, would rebel from Axis control and participate in the Dukla offensive from the south. The East Slovak Army Corps (Axis-power-aligned) was designated with the key role of opening Dukla Pass to the advancing Soviet forces. The agreement was forged in secret negotiations between Soviet Colonel V. Talskiy and the East Slovak Army Corps

- The German defenses Krosno-Dukla were assessed by Russian intelligence to be weak

Advantages

- The attack would cut the German First Panzer (tank) division main lines of communications with German Army Group North Ukraine

- The pass allowed easy passage of large amounts of equipment

- The pass allowed access to partisans and the plains of Hungary

- The 38th Soviet Army possessed an unusually large number of tanks and an extremely high amount of armaments

Disadvantages

• Neither the brass nor staff had experience in mountain fighting (Konev)

• No mountain-specific equipment

• Deviation from initial plan.

• Minimal aviation support was a result of lack of fuel

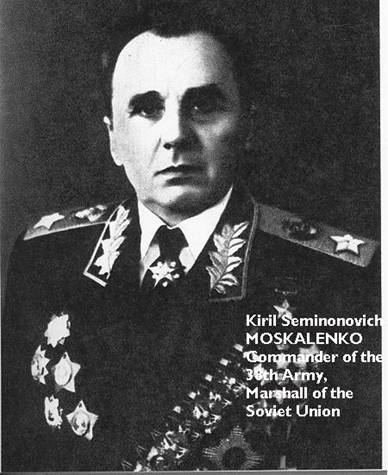

Tactical Plan: On September 2, Stavka ordered an assault on Dukla Pass to begin no later than September 8th, in general direction of Stropkov- Medzilaborce. The task of assaulting the mountain pass was given to General Kiril S. Moskalenko's 38th Army and the attached 1st Czechoslovak "Free" Army Corps. The 1st Guard Cavalry Corps, 25th Tank Corps, and secondary units would then effect a deeper penetration to insurgent territory. The Red Army expected the East Slovak Army Corps would meet up with them in 3-4 days.

Tactics included:

• Rapid advance through defenses by the 25th Tank Corps and 1st Guard Cavalry

• Substantial use of partisan informants

• Primarily invade via roadways

• Aircraft for reconnaissance and to eliminate artillery and mortars in the mountains

• Artillery for the initial assault

• Tanks used primarily to support infantry after artillery “softens up” enemy positions

• Flank attacks – an end-run around the side or back of the enemy position to isolate or cut off enemy troops.

• Quick shifts in attack positions

Planned Timeline (Konev)

Day 0 – initial assault beginning near Krosno)

Day 2 – Tylava, Poland (within a couple kilometers north of the Dukla Pass)

Day 3-4 – Meet up with the East Slovak Army Corps 1st and 2nd (north of Stropkov) and guerilla detachments

Day 6 – Reach Presov (90-95km advance)

Leadership

| Profile: General Kirill Moskalenko | |

| The Soviet 38th Army was led by General Kiril Moskalenko. He was a career officer, joining the Red Army in 1920. In 1941 he had been the Commander of an Anti-Tank Brigade at the Battle of Kursk and also fought at Moscow and Stalingrad. In 1942 he became the Commander of 40th Army and in 1944 was assigned to lead the 38th Army and the attached First Czechoslovak Army. |

1st Czechoslovak Army Corps

On July 18, 1941, the Soviet Union signed an agreement with the Czechoslovak government-in-exile allowing for the formation of Czechoslovak troops on Russian soil. On December 8, 1941 the Soviets designated the town of Buzuluk, Russia as the training camp for what was then known as the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Battalion. Buzuluk was located approximately 180 kilometers from Kuybyshev in the Orenburg region.

The greatest number of the Army Corps came from the least likely element: the Carpatho-Rusyns sent to the gulag for illegal border crossing.

The First Czechoslovak Army Corps was initially led by General Jan Kratochvíl who had been flown in from the London-based Czechoslovakia government in exile. He was later succeeded by General Ludvik Svoboda.

After the war, General Konev was clearly impressed with the actions of the First Czechoslovak Army: “we noted a remarkable exhibition of high valor in Czechoslovak soldiers. We were pleased with the fact that the Czechoslovak soldiers were included in military struggle against the German fascists as they boldly attacked enemy troops.”

Initial Assault – Fighting in Poland

On September 8th a 2 hour 5 minute extremely heavy artillery barrage was launched against the Germans in Poland. The 38th Army troops moved at first with little resistance, advancing 14 kilometers the first day. The initial line of attack was from the Poland villages of Iwla to Tylawa. This region is about 15 km north of the Carpathian mountain ridge, roughly from the towns of Sanok to Sambir. By nightfall the German resistance began to stiffen and Moskalenko still had not heard the expected communications with the East Slovak Army as had bee agreed.

On September 9th, the 1st Czechoslovakia Army Corps was committed to battle. However, in many sectors the same roads were used to deploy the 1st Czechoslovak as well as the Calvary troops, and this congestion hindered troop advancement. The Soviet 107th Rifle corps advanced 4-5 Km under the command of General Andrei A. Grechko.

The attack centered in villages of Mszana, Smerczne, where steel reinforced bunkers had been placed by the Germans. The Czechoslovak Army troops were initially too far off in water-clogged roads to participate in the first day's fighting. The Soviet 38th Army quickly bogged down in German defenses near the village of Dukla, in Poland. By September 10th the Soviets had penetrated Krosno but a second line of German defense stalled troop movement.

The fighting in this region was about 15 to 20 KM deep and 15 to 20 km wide. In addition to German defense with armor, infantry and artillery, thousands of land mines had been planted.

Heights of land posed obvious problems. “Battles for Height 534 and Mount Hyrowa/Girova were critical. These mountains were of higher range than others. The Germans occupied a commanding view, and their artillery afforded the offensive side no rest. The 4th Battalion's radio unit was destroyed by German artillery, and the battalion was isolated. Fortunately for its members, Svoboda had a thorough knowledge of the geography of the Carpathians, and dispatched the necessary forces to rescue them. Height 534 changed hands several times. Mount Hyrowa proved equally formidable, with an isolated German unit pouring fire on the Czechoslovaks advancing to rescue the Katyusha battalion. The Katyushas consequently directed their own fire power against this position. [Ivan] Kurbatov [a Soviet artilleryman] later noted that every fire point of the Germans "needed to be smoked out.” Source: Baumgarten

Intelligence Missed

Photograph: Konev consults with 38th Army Commander Moskalenko

On September 10th, General Konev arrives personally to inspect the situation. He recognized that the Slovak troops were not coming up from behind as expected.

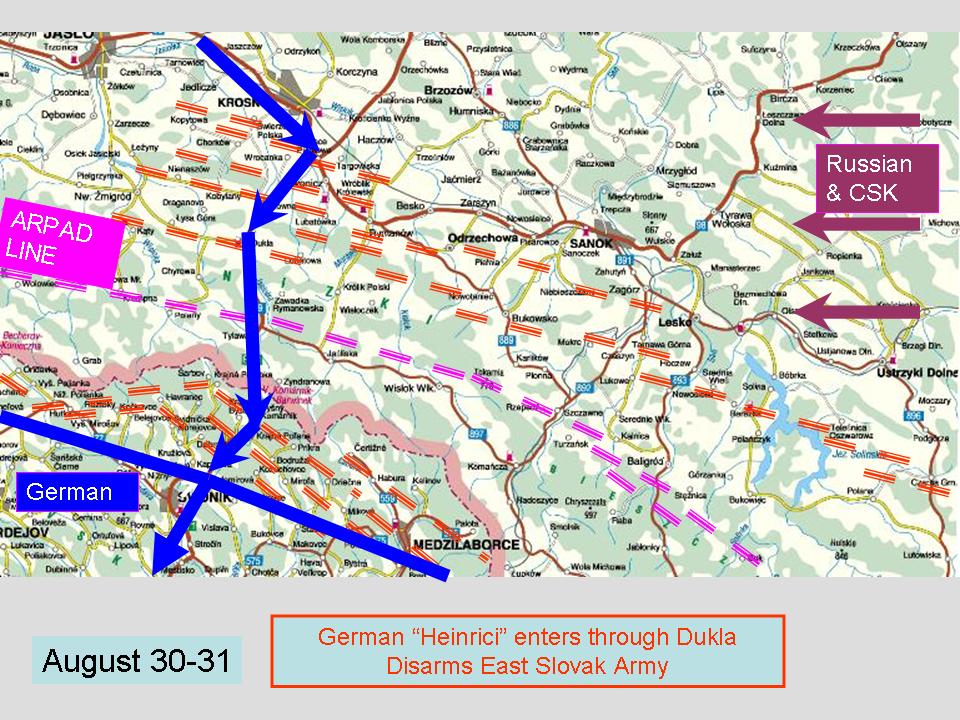

It was uncovered later that on August 27 the German had prepared plans to disarm the Slovak Army – code name “Kartoffelnernte”. This was largely in response to German intelligence suggesting the Slovak Army was not to be trusted in light of the SNP uprising. The deployment on August 30-31 of Army Group “Henrici”, moving south through Dukla pass went entirely undetected by Soviets.

The East Slovak Army Corps had been stationed in Presov and environs. Their commander, General August Malar lost his nerve for the uprising. Malar sent signals to his troops that the “Heinrici” troops invading Slovakia would take no punitive measures against the Army and were thus not to respond. Within 24 hours Heinrici had disarmed the East Slovak Army Corps, arrested Malar and taken up defensive positions. Only a few units broke away.

The Soviets had assumed the Slovak Army Corps was still in place, depending a great deal upon intelligence gathered by partisan operatives who smuggled across the border to provide updates.

During initial assault, Germans quickly brought in reinforcement troops and equipment, almost doubling its forces to six infantry and two Panzer divisions in a matter of days. Six days to Presov turned into four months.

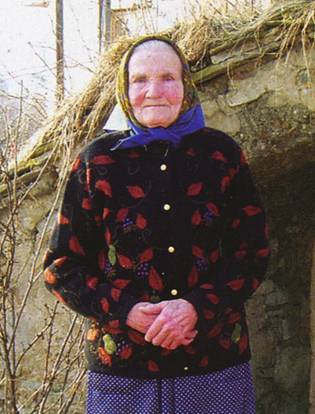

| Kapišová , August 29 – A German aircraft swooped overhead. Anna Maššová, and her husband, had four children aged 21 months to 10 years. “We ran to the forest, we lay down in a creek bottom and covered ourselves like this” She ducks her head toward the table and covers it with her arms. “Then we waited. When we returned, there were Germans everywhere! They were moving into the root cellar. One soldier said ‘where have you been you partisans?”, but then another, who spoke Polish, said, ‘what’s your name? And I said “Anna’, and he said ‘Anna, don’t be afraid, You’ll be all right’, he took a cross from around his neck and showed it to me.” Anna is a devout Greek Catholic and this gesture is remembered fondly “he was a farar” she says using the Slovak word for pastor for parish priest. Credit: Slovak Spectator/Spectacular Slovakia |

|

Profile: Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici | |

| Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici, 1886-1971, was a German career officer. The Heinrici family had been soldiers since the 12th century. On 18 August 1944 he was assigned Commander-in-Chief of newly-formed Army Group “Heinrici”, consisting of the First 1st Panzer Army and the Hungarian 1st Army. Heinrici had a long-standing reputation as a master of defensive tactics. In effect, the Soviet 38th was unaware that it was now up against one of the best that Germany had to offer. |

Stalled – Konev Acts

According to Konev, the situation required a high coordination by the commanders of the corps and their staffs, and he concluded General Kratochvil of the First Czechoslovak Army Corps was not up to the task. He noted that the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps was not well coordinated with the actions of the 38th. Oftentimes, the 1st Czechoslovak army was confused, in large part because their commander remained substantialy distanced from the fighting. “In spite of Kratokhvil’s long tenure in the army reserve corps, he was not was entirely prepared for this battle, which requires great responsibility and the need to personally lead troops in the battlefield.” – Konev’s memoirs

After a strongly-worded discussion with the Czechoslovak Government in exile, Konev replaced General Kratokhvil, with Ludvik Svoboda on Sept 10th to command a force 10,000 men strong.

Profile: Ludvik Svoboda | |

|

Born in Moravia. Called to Austria-Hungary service, but defected to the other side during World War One. Much to the chagrin of the Soviet Generals, Svoboda spent much time on the WWII front lines, making it occasionally difficult to find him. He did however have the full faith and confidence of the Soviet Army. "At the time," Svoboda said, "I had to see the battle zone with my own eyes. I don't understand how you can command forces without having an idea of the terrain along the line of advance. So I went directly through the forward units to the attacking forces. And there I saw that it was essential to inspire the troops--to set a personal example in combat.” |

Redouble Effort – Progress in Poland

The Soviets then reinforced their positions with the 4th Tank Corps, additional Czechoslovak pilots, the 2nd parachute brigade (700 men, 104 tons equipment), and the 1st Czechoslovak fighter regiment.

Konev selected a gap of less than 2,000 yards on Moskalenko’s flank, west of the village of Dukla and ordered First Guard units to a flanking attack on the night of September 12th. They were quickly closed off by German troops to their rear. Recognizing their entrapment, they single-handedly fought their way out the encirclement suffering loses of 60 percent.

On September 17, 1944 the Prime Minister of Slovakia declared war on Russia, without Parliamentary ratification, suggesting a further unraveling of the government. By September 20th, the Soviets had advanced southward and taken the stronghold village of Dukla, Poland.

Also on September 20th, the village of Kalinov became the first Czechoslovakia village liberated by the Soviet 128th Guards Rifle Division. Kalinov is about 15Km southeast of Dukla Pass. While some historical material claims the village of Vyšný Komárnik was first liberated in Czechoslovakia, the data does not support his. Kalinov, a village just across the border, appears to have been a small puncture across the mountains, and held in isolation until the troops further advanced in early October. A commemorative plaque noting this event is found in the village, listing the date of liberation as 21 September.

On September 20th Konev added the 127th rifle division and the 12th mortar brigade. The troops were within 2 to 10 km of the mountain ridge. (Konev)

By September 26th the Red Army had crossed the Arpad line – which roughly includes Villages of Mszana , Chyrowa, Tylawa, Olchowiec, Ropianka, Wilsznia, and Smereczne. Wilsznia and Smereczne were obliterated in the fighting. Fighting at the pass had begun.

Partisans

“Many individuals ignored danger and passed across the front line to the Soviet Army side with reports of the positions of the German occupiers. Others acted as scouts.” – Under Snina Stone

“The Red Army had been supporting the training and supply of partisans since early 1944. Others organized outside of Czechoslovakia were airlifted in the summer.

In April 1944 the Ukrainian Communist Party announced its decision to aid the Czechoslovak cause by setting up a special training program for partisans who would be dispatched to Slovakia. The organization was entrusted to the Ukrainian Partisan staff, which was assisted by Rudolf Slansky, special representative of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. About a hundred Czechs attended the first training course, as well as a number of Polish partisans. The initial plan called for ten partisan groups (with ten to twenty men in each group) to be air-dropped into eastern Slovakia. The Soviet command meanwhile began bolstering the regular Czechoslovak military units already fighting on the Eastern Front. The 2nd Czechoslovak Parachute Brigade was likewise trained for specialized warfare behind German lines. On the night of July 26, 1944, the first partisan detachment was parachuted into Slovakia in the Ružomberok area, further to the west than originally anticipated. This unit was commanded by a Red Army captain named Piotr Velitchko and it immediately began setting up base areas for additional partisan detachments.” Source: Baumgarten

Some of the Slovak Army fled and attempted to break through to the join the Red Army. When this was not possible, they became partisan fighters.

“The organizing of the partisan movement reached to the community Pcoliné-Pichne, not far from Snina. The partisans occupied the community by the 12th of August, 1944, and subsequently they camped in the nearby woods, so that -- with the cooperation of the local inhabitants – they created an independent partisan division. There were large [military] actions near the community in September 1944, when German units disarmed members of Slovak divisions. In the vicinity of the community, members of the Prokopinkov partizan detachment attempted to punch through the German front lines and to fight their way through to the Soviet army, and soldiers under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Vogol became partisan fighters. Many citizens of Pichne provided aid to the partisan movement.” – Source: Under Snina Stone

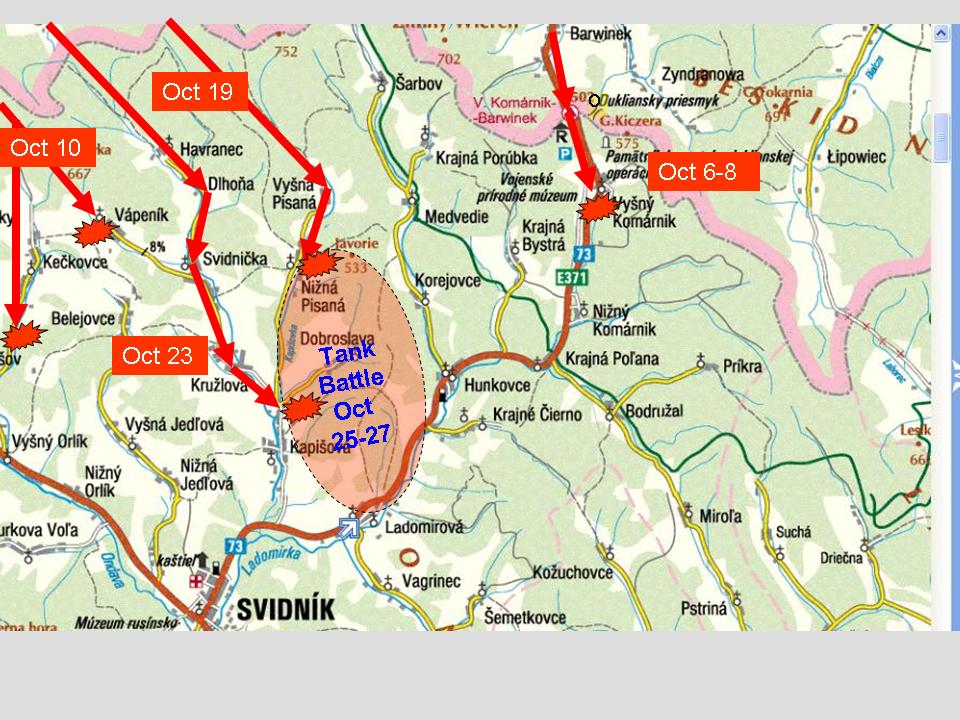

October 6th - 8th

At the end of September, through fog and heavy rain, 67th rifle division and 31st Tank Corps of the 38th army and the Czechoslovak 1st Army Corps resumed its advance. On October 6, it cleared the south end of the pass. Its entrance into Slovakia came at a staggering cost. General Vedral, commander of the 1st Brigade, was killed by a mine less than one kilometer after crossing the border.(46) ...October 6 was thereafter designated as Czechoslovak Army Day. Since the breakup of Czechoslovakia in 1993, it now remembered in Slovakia as Liberation Day. Source: Baumgarten.

The troops were able to advance as far as Vysny Komarnik, the first village south of the pass before their advance stalled on October 8th.

The Rain

Continuous rains began to fall in October. Mountain paths and roads became impossible to mechanized as well as horse-drawn vehicles.

|

“"How do you think it felt seeing so many young men dying all around you and blood and dead bodies lying on the white snow? …Those were difficult fights. We fought day and night. It was painful and terrifying" |

|

Ján Jurcišin, 1st Czechoslovak Army Source: Slovak Spectator |

Homeland Evacuation

“Often the people found themselves in the fields and roads, where they remained during the entire period of bombardment, which resulted in the loss of human lives.

It was a cold and damp November, when the fascists began to drive the people from their homes. Many of those hid themselves in the nearby forests and some remained hidden in barns. The predominant part of the population, however, was evacuated to the west as far as the regions of Liptov and Považie.” Source: Under Snina Stone

Dukla and the SNP

At the end of September Heinrich Himmler arrived in Bratislava. He recognized that the potential taking of Dukla posed a great threat to Germany should the army meet up with the partisans. Himmler sets in motion an accelerated plan to crush resistance. On 18 October Germans invaded Slovakia from all sides. Originally, Himmler’s plan was to isolate the insurrection with local troops and let it bleed to death, over a slower period of time.

While it may seem a noble gesture on the part of Russia to "librate" the people of Czechechoslovakia, a large volume of evidence suggests that Stalin had no interest in the independent nationalistic aspirations of it's people. It's not clear that he was at all interested in aiding the SNP, but strictly used it as part of his larger vision. His objective to control and dominate this region became legend for the following 50 years. Read the work of Mr. Peter Vlcko and decide for yourself.

Breaking the Stalemate

On Oct 8th the front had stalled at Vysny Komarnik unable to progress south of Dukla Pass. On October 10th, Konev moved to a westward flanking attack across the mountains to the villages of Vapenik and Keckovce. However, progress could not be made past these initial villages. On October 19th, the Red Army moved it’s assault northward about 5 KM to the villages of Vysna Pisana and Svidnicka and advanced to Nizna Pisana by the 23rd.

Tank Battle: October 25 - 27

“On October 25th, the rainfall which had impeded the Allied advance began to subside. At 10 a.m. the Soviet side began and 80 minute artillery barrage and air attacks. This followed by advance of the 305th Soviet Rifle Division and the 12th Guards Tank Brigade.

Advancing through a narrow mountain valley, they were unable to develop any coordinated line. Yet they entered the village of Nizna Pisana and engaged the German Mark IV tanks successfully. Breaking the enemy's resistance, the 12th Guards Tank Brigade moved 1.5 kilometers south of the village.

Here it came up against the German artillery and the land mines. When night fell, the illumination of the sky caused by German artillery fire enabled Soviet engineers to destroy the mines planted in the road. The advancing Soviet infantry captured two German artillery pieces and five tanks.

On the morning of the 26th, Soviet aircraft struck hard at the enemy's artillery and mine battalions. Soviet infantry and tanks advanced once again. Yet in the area between the villages of Kapisova and Dobroslava the Germans were particularly well entrenched. Their artillery batteries hurtled an estimated 75,000 shells against the Soviets. Consequently, all the Soviet tanks committed to the Valley of Death were destroyed. “

Source: JOZEF RODAK, Ph.D.

|

One day, the Germans waved Anna over to the root cellar and hander her the telephone. “All I could hear were shooting and explosions’ she said. The battle to the north had begun. The Germans went up to the valley to join the fight, but didn’t return. “We had seven cows and in the morning I got up to milk them. Then I saw the farar come out of the woods. His clothes were torn and he was all scratched up. They had crawled on hands and knees back along the creek. They asked me for the milk. I had just taken from the cows and I gave it to them. Then the farar passed around his had and insisted on paying me for the milk. “It’s time for you to leave” he said. “The battle is getting too near.”

|

|

Around the first of October, the family buried stores of grain, honey and tvaroh cheese for the future and headed south to a farm near Chmelovo on the road to Presov. Among the dead of Hunkovce was Anna’s mother. “We don’t know how she died.” Anna says. Maybe the Germans shot her or maybe the Soviets. Maybe she was just killed in the shelling. But she died in the forest and because of the fighting and the winter no one could retrieve her body. In the spring my brothers went to find it. They wrapped her in a sheet and buried her in a bomb crater,” she says, still grieving 60 years later. |

Anna Maššová, - Source: Slovak Spectator |

Other Advances: Ruske

From October 3rd to 11th the advanced further down the Carpathian ridge to the south of Dukla. Starting at Roztoki Gorne, Poland the 67th Rifle Division and the 129th Guards began their attack towards the now-defunct village of Ruske, Slovakia (north of Starina Reservoir) mastering strong points at heights 1046 and 1098. The 129th Guards rifle division, attacked from northeast southward. The 67th Rifle Division attacked along the right flank (moving west to east) towards Ruske.

The troops primarily advanced through the forests. These troops advanced without artillery support, which remained 7-12 KM away from the fighting. The biggest surprise to the Germans was that the attack included T-38 tanks, which climbed to a high point and attacked downward toward the enemy which had dug in just north of the village of Ruske, with artillery. The Germans expected infantry, and the crossing was taken by the 167th. The biggest challenge was the bad weather and complex mountain conditions. According to Konev this demonstrated the ability of tanks to fight in mountainous terrain. It is said this was the first time in warfare that tanks were successfully utilized in a mountain attack.

Sources: Soviet Army Operations and General Andrei A. Grechko

"We advanced upon Slovakia and came to Dukla. The battle there was pretty tough. It was cold and the weather was foul. There was a lot of snow. We had a lot of high quality military equipment, fiats and Studebakers and what have you; but we just had to leave it, along with our provisions and supplies, and go on by horse. And then on that hilly terrain I hadn't expected to encounter even the smallest fortification, but there were bunkers!” |

|

Josef Zeleny , 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps |

Run!

As the fighting approached, women, children and the elderly fled to cellars, storerooms or nearby woods. They dug holes, and remained for days or weeks until cessation of fighting.

Liberation

The Mašša family returned to Kapišová in early April 1945. “It was terrible” Anna says. “My brother warned me not to go, but we wanted to go home. The snow had melted and there were dead bodies everywhere! All over the Valley! Russians, Germans, horses, cows. Everything was dead, just lying there. It smelled terrible. There were broken tanks all over. We found only seven houses left standing in the village and one of them was ours. |

|

When they reached home, they found six Russian soldiers living there and 20 housed at the neighbor’s place next door. They had been left behind to repair the damaged tanks. She also found that everything the family had owned was piled in the yard, broken and destroyed, and all the food they had buried had been discovered except for a single store of corn.” |

Anna Maššová, Slovak Spectator |

Casualties

• 138,000 – Dead, Wounded and Missing

• More than 46,000 Soviet, Czechoslovak and German soldiers died

– 6,500 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps, (60%)

• Over 93,000 Soviet and Czechoslovak troops were wounded

Impact: Snina Region

• 918 homes were totally destroyed

• 2,217 homes heavily damaged

• 11 villages were 90% destroyed

• 14 villages 50% destroyed

• 55 bridges destroyed

• 250 civilians were killed during battle

• 180 civilians were seriously injured by land mines alone.

The Immediate Outcome

• Combat Group “Heinrici” retreated nearly 200Km toward the west. Soviet troops took 31,360 prisoners.

• Svidnik was virtually destroyed.

• Czechoslovak 1st Army Corps – Over 9,000 men between ages of 20 and 35 joined after October including Slovak Army defectors who fled in advance.

Progress Westward

1944

• October 28 – Uzhorod liberated, East Carpathian Operation complete

• November – South to Sobrance, Michalovce

• November 26 – Snina region liberated completed

• January 5 – Presov liberated (5 months late)

“When it became obvious that the Slovak Republic was on the losing side of the war in 1943, some Rusyns began to organize. The first partisan unit was formed in the Presov Region that year, and eventually the movement encompassed some 37 villages in the northeast. In September the Carpatho-Russian Autonomous Union (Karpatorusskii Autonomnyi Soiuz Natsional'nogo Osvolozhdennia-KRASNO) was organized. It maintained contact with both the Slovak resistance movement and the Czechoslovak liberation movement abroad. KRASNO

consequently welcomed a declaration by the Slovak National Council in October

1944, which stated that the resurrected Czechoslovakia should consist of three

equal nations--Czechs, Slovaks and Carpatho-Rusyns.

Hammered by the onslaught of the Soviets and 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps in front of them and the activity of KRASNO partisans in the rear, the Germans began retreating. Svidnik was heavily damaged in the fighting, and the Germans torched much of the area as they withdrew. Svoboda was nonetheless hailed as a liberator when he entered the town, and was declared an honorary citizen of Svidnik.”

The composition of the 1st Army Corps again underwent a significant change during its westward advance. Its Slovak element had been considerably depleted by the detachment of the 2nd Czechoslovak Paratroopers to aid the uprising. Many Carpatho-Rusyns had been killed in the battle for Dukla Pass, although their numbers were easily replaced by new recruits in northeastern Slovakia. Yet, as Svoboda's army pushed westward, the majority of the 1st Army Corps became Slovak.” - Source: Vladimir Baumgarten

Left Behind

• Poverty, Unemployment

• Healthcare – Not addressed in the east until 1948

• High Infant and Mother mortality

• Tuberculosis, whooping cough, scarlet fever, and intestinal typhoid, diphtheria

• Isolation

• Lack of Education

• Ľ population illiterate

• Rebuilding Homes

• Bandits

• Reports of people living in tents as late as 1947

Wooden Churches

Of the 27 wooden churches in Slovakia which were declared National Cultural Monuments in 1968, eleven are located within Svidník District. Most of these churches date from the 18th century.

Churches Damaged

-

WWI

– Kapisova

– Keckove

– Hutka, Vyzny Komarnik, Nizny Polianka, Dlhova

• WWII

– Ladomirova - Iconostasis damaged

– Nova Polianka suffered extensive damage, razed 1961, reproduced at the Svidnik Open-air Museum

– Nizny Orlik

– Many Poland villages west of Dukla town were totally decimated as the battles fought through their settlements

– Often the government took the church bells and had them melted for war machinery. Citizens sometimes took covert action to bury them for protection.

Czechoslovak Army Monument – Vysny Komarnik

It is said that this memorial is now neglected. Thousands of schoolchildren used to visit annually and recite their oath of allegiance. 565 Czechoslovak Army Soldiers are buried here.

• Avenue of Dukla Heros

• Lookout Tower (1974)

• Cracked Heart Memorial – to General Vedral-Sazavsky

• Svidnik Military Museum (1965)

Cemeteries, Monuments

I've never seen an integrated list of cemeteries dedicated to the war dead in this region. Thousands of soldiers from far away fought, died and were buried here. So here's a start. Please send me other cemeteries that you may know of.

• Soviet Cemetery in Svidnik (1954), 9,000 Soldiers

• Hunkovce Cemetery (1995) - 2,648 German soldiers

• Zborov – 1,137 German Soldiers

• Rymanowe, Poland - Monument to the Soviet Army

• Dukla, Poland Cemetery, 8,100 Russian, Czechoslovak, Ukrainian Polish Soldiers

• Vyšný Mirošov - 250 German, Austro-Hungarian and Soviet soldiers from the First World War

• Nižná Polianka

• Radvaň nad Laborcom

• Medzilaborce

• Stakcin – Monument to the Red Army

-

Zboj - I have been informed by a local that a WWI military cemetery exists in the woods near Zboj. It is overgrown and unmarked. I would love to learn it's precise location.

Others:

Military Cemeteries

-

Kolbasov (33 buried soldiers)

-

Nová Sedlica – Vasilcova lúka

-

Osadné (1025 buried soldiers in the crypt at in the Orthodox church, 1473 buried soldiers near Greek-Catholic church)

Parihuzovce (480 buried soldiers)

-

Príslop (89 buried soldiers)

-

Runina (90 buried soldiers)

-

Snina (130 buried soldiers)

-

Stakčín (959 buried soldiers)

-

Topoľa (240 buried soldiers)

-

Ubľa (41 buried soldiers)

-

Ulič (71 buried soldiers)

-

Zboj (203 buried soldiers)

In the flooded villages: Ruské (100 buried soldiers), Smolník (124 buried soldiers), Veľká Poľana (340 buried soldiers)

On the hill Predný Hodošík (2200 buried soldiers) – The highest World War I cemetery in Slovakia (825m above the sea level)

War monuments, war Tombstone

-

Nová Sedlica, on the border edge in NPR Stužica – a monument to soviet soldier A. Gladyšev, who was killed in World War II

Snina and Stakčín – a Cenotaph for soldiers from World War I and World War II

-

Starina –under Darnov - a Cenotaph for soldiers from World War I

-

Starina – under dam of reservoir – a Cenotaph to the weapon engineer from World War II

Uličské Krivé, above village in Oblazy – a monument to soldier Linhart who was killed in World War II

-

Near flooded village of Ruské in Ruské Sedlo - a monument to liberators from World War II and a rotunda to killed soldiers from World War I in the military cemetery in Veľká Poľana

Afterwards

Here's a brief synopsis of what happened to the major personalities of the Carpatho-Dukla operation:

Heinrici

• 20 March 1945, Heinrici succeeded Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler as Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Weichsel [Vistula] on the Eastern Front.

• 17 April 1945 responsible for the defense of Berlin

• 29 April 1945, Generalfeldmarschall Keitel dismissed Heinrici for conducting an unauthorized withdrawal.

• 28 May 1945 Surrendered to British Troops in Flensburg, in British Captivity

• Died 1971

General Kiril Moskalenko

• Commander of 38th Army until end of war

• 1955 - Marshall of the Soviet Union

• 1960 Commander in Chief of Strategic Missile Forces

• 1962 Inspector General Ministry of Defense

• Hero of the Soviet Union

• Died 1985

Svoboda

• Arrested on a rumor

• 1952 Stalin: "Please set General Svoboda free."

• Not allowed to resume military career, became a book keeper

• 1954- Elected to Assembly

• 1968-75 President of CSSR (Czechoslovak Socialist Republic)

Died 1979

Protected Areas

These regions, where some the worst fighting occurred have now evolved into protected natural reserves, forests and parklands. The area is still quite remote, distance from most modern settlements, difficult to reach. Most foreign visitors are naturalists, hikers and those who seek a remote, natural environment.

• Stužica Preserve – Slovakia

• Národný Park POLONINY (Poloniny National Park) 1977

• Bukovske Vrchy Natural Reserve (of Poland)

• East Carpathian Biosphere Preserve

• Carpathian EcoRegion Initiative

For Further Reading

• David Glantz (Forgotten Battles of WWII)

-

Mr. John Kulhan, Soldier, 1st Free Czechoslovak Army Corps, Battle of Dukla Pass

COMBAT GROUPS ENGAGED IN THE CARPATHO-DUKLA OPERATION, August-November, 1944

|

Source: Karpatko Operation battle map, Sep 8 to Nov 30 |

Michalovce-Snina-Medzilaborce

|

- MOSKALENKO, Marshal Kirill Semenovich, On the South-West Front 1943-1945, From the series "World War II Research, Reminiscences and Documentaries", Publishers "Nauka" (Science publishers, Moscow), 1972 (Russian)

- Grechko, Marshal Andrey Antonovich Cherez Karpaty (Through the Carpathians), Military publishing house of the Ministry of Defense of the USSR "Voenizdat", Moscow, 1972. (Russian)

- Konev, Zakharov, Zheltov, Grechko, Sharokhin, The Great March of Liberation, Telegin, Progress Publishers, USSR, 1972 (Russian)

- Vydavatelstvo Osveta, Vychodoslovenske Vydavatelstvo & Dukla Museum in Svidnik, "Dukla", 1979, CSSR Below Snina Rock (1964) - (Translated from Slovak to English)

- Slimák, Vladimír "Below Snina Rock", 1964 (Translated from Slovak to English)

- Erickson, John "Road To Berlin", Westview Press, 1983 ISBN 0891587950 (English)

- Vladimir Baumgarten, PhD, THE CARPATHO-DUKLA OPERATION, 2005 – Friends of Dukla Pass (Biblio)

- Moskalenko, Marshal Kirill Semenovich, On the South-West Front 1943-1945, Chapter 16: Along the roads of Poland and Czechoslovakia (see above) (Russian)

- Konev, Ivan Stepanovich, Notes of the Front Commander, (Science publishers, Moscow), 1972 (Russian)

- Petrov, S. I. Svoboda L Z, Grachev Buzuluku do Prahy. Nase Vojsko (Slovak)

- Svoboda, Ludvik, Freedom from Buzuluk to Prague, 1963, M.: Voenizdat, 1963 (Translation from Czech to Russian)

- The Soviet Union’s Role in the Slovak National Uprising, Vlcko and Vlcko, 2009

Further Reading

CzechPatriots - Czechoslovak military units in USSR (1942-1945)

- GENERAL LUDVIK SVOBODA: COMMANDER OF THE 1ST CZECHOSLOVAK ARMY CORPS, Vladimir Baumgarten (excellent reference list)

- Svidnik, Slovakia

- Major General Frantisek Fajtl

- Register of the Czechoslovakia. Armada. Ceskoslovensky Armadi Sbov v SSSR, 1. Miscellaneous Records, 1941-1945 (California Online Archive)

- Ludvik Svoboda

- Russian military memoirs online: http://militera.lib.ru/ (Russian)

Links to off-site webs will open in a new window. Please disable your pop-up stopper.

Last Update: 15 November 2020 Copyright © 2003-2021, Bill Tarkulich